50 years later: Memories of an activist and Fisk University exchange student

Tom Herbert ’66 (fifth from left) had a transformative experience as an exchange student the spring of his sophomore year at Fisk University in Nashville, Tenn.

Tom Herbert ’66 responded to “The March for Freedom: Civil Rights Activists Look Back,” in the spring Cornell Report with this account of his experience as an exchange student at Fisk University.

In the fall of 1963 I was a sophomore at Cornell College, and I heard about the exchange program the college had with Fisk University, a predominantly black college in Nashville, Tenn. One of my older brothers had gone to France on a junior year abroad program from Carleton, but I didn’t want to be gone for a whole year, not wanting to miss a season of cross country running. I inquired about the program, wrote my parents, and got very positive support from my mom and lukewarm support from my dad—remember this was the time of church explosions, missing civil rights workers, violent responses to Freedom Riders, and more.

I spoke with Howard Troyer, dean of the college, who was in charge of the exchange, and told him I wanted to go during the second semester of my sophomore year. He told me I would have to get letters of support from my parents. After a bunch of letter exchanges and a trial visit required by my dad on my way home for Christmas, I got the OK to go in January 1964. My memories of my arrival and first months at Fisk are vague. I was in DuBois Hall with a roommate. His roommate had taken my place at Cornell. Having a roommate didn’t last long. I am not sure why he moved out, but I soon found myself in a single. Luckily for me I found Robert Moore.

Robert, from Tuskegee, Ala., was a year ahead of me and for some reason took me under his wing. He introduced me around and included me in his social circle. He was one of the main reasons I had such a pivotal experience at Fisk. There were also other exchange students at Fisk. They came from Pomona, Adelphi, Beloit, St. Olaf, Colby, and a few others. I consciously chose not to hang out with them too much. There were also foreign students there, primarily from African nations. I don’t think all of the Fisk students enjoyed having exchange students on their campus. For many, the campus was a safe place where they could be themselves and not worry as much about the white norms and values they were usually surrounded by.

I wanted to get involved in activities, so I joined the Fisk track team as a one-mile and two-mile runner. Fisk had no track, so we trained on the football field. The distance runners trained by running around the outside of the field. It was there, running with some teammates in practice, that I vividly remember experiencing “hate stares.” Earlier that semester I had been walking off campus with Robert and he started laughing. I asked what was so funny and he asked if I had seen “that.” When I replied in the negative, he said I had just missed a “hate stare.” I knew what they were from reading “Black Like Me,” and I soon was able to easily recognize them.

By the middle of March demonstrations were starting. Nashville still had several segregated restaurants, including Morrison’s Cafeteria. I wrote to Dean Troyer telling him that the demonstrations were starting, and while I wanted to participate, I didn’t want to do anything that would jeopardize Cornell’s reputation. He wrote me back a long letter, basically saying that the college had picked me to represent them and the college would back whatever I decided to do. That letter (reproduced below) gave me goose bumps then and brings tears to my eyes now.

In April the Rev. Martin Luther King came to the campus. He spoke to a packed house in the gymnasium. Mine seemed to be one of the few white faces in the crowd. I remember being so moved by what he said that if he had told us to march through a gym wall, I was ready to ask, “Which wall?”

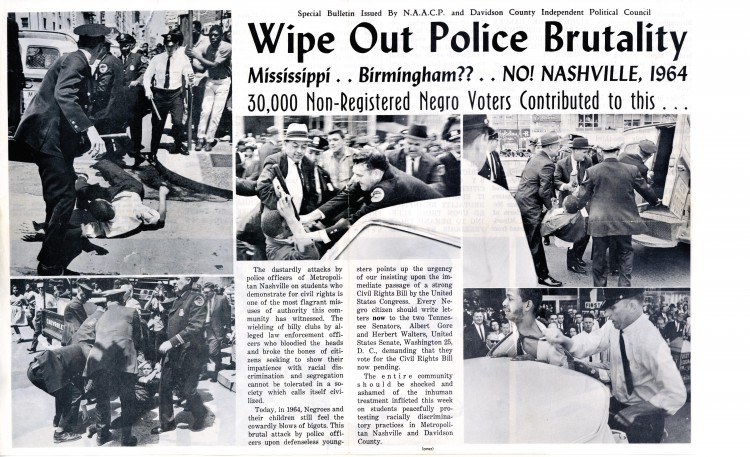

My friend Robert wanted nothing to do with the demonstrations. I would find out why later. Several days after King’s speech I went to a Nashville court downtown to observe a court hearing for several protesters who had been arrested on “John Doe” warrants. Arrest warrants were supposed to have actual names on them, but these were all “John” or “Jane Doe.” While there I befriended the family of one of the protesters. They had two young kids who I fooled around with while we waited out the court proceedings. After court ended we heard sirens. I went outside where the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee had organized a protest. The kids had sat down in the middle of the main street. Fire trucks and police were there. I was standing on the sidewalk watching when the fire hoses were turned on. The police waded in with billy clubs. Chaos erupted. I watched with horror as the police beat people and repeatedly clubbed one man on the head and shoulders as they pushed him into a paddy wagon. I looked around and suddenly found myself standing next to the two young black kids I had befriended in court. We were holding hands, while around me I could hear some whites yelling, “Get that nigger! Beat that one!” I remember having a sort of out-of-body experience, seeing the riot taking place and seeing me holding hands with two black kids in the middle of a full-blown race riot.

A few days later a march from Fisk was organized to demonstrate at Morrison’s. It was to be a peaceful, respectful march. When someone came in or out of Morrison’s, the line was to stop and make room with no comments made. I remember as we marched down, singing songs from Odetta’s Freedom Trilogy, an elderly black woman sitting on her porch looked at us and simply said, “Thank you.”

We got to Morrison’s and started circling around the block. I had just gotten past the front door when the order came to break off and start back. The police had come and started arresting leaders. They were also arresting all white protesters. Apparently it didn’t look good to have an integrated protest march. As we were marching back, a group of Fisk basketball players surrounded me and told me to lean over. Police cars were patrolling the line, looking to arrest more whites. I managed to get back to campus free and clear, unseen by the police. But changed.

We decided we would plan a big march and protest for the Friday before Mother’s Day. Our posters read “M.O.M.”…“March on Morrison’s … Give your Mom a real Mother’s Day present!” We hoped to have several hundred students join with us for the biggest march so far. I worked with the Fisk student body president, Esther Pearl Roberts. On the Thursday before the march I wrote my mom.

The town I was raised in, Upper Montclair, N.J., was a de facto segregated town. Only white people were allowed to buy housing on one side of town—it wasn’t a law, just an understanding. My mom fought to change it, and as a result of her stands for equality she received death threats.

She never believed in Mother’s Day, always saying it was just a way to get people to spend money. In the letter I told her of our plans and that this was my Mother’s Day present for her and that by the time she got the letter, I would most likely be in jail, knowing that whites would be arrested first. I sent it off Air Mail Special Delivery.

On Friday morning we started to gather at the student center. We had put posters up all around the campus, urging other students to join us. We encouraged them to bring their books so observers would know we were students. Police cars started driving through campus, keeping an eye on us. At noon, the time we were supposed to start marching down to Morrison’s, a large crowd had gathered at the student center.

Esther Pearl and I looked at each other and said we should start. As we left, there were only about 10 of us marching. We agreed to go anyway. About three blocks down the street I looked back. I couldn’t believe what I saw. I tapped Esther Pearl and told her to look back. You couldn’t see the end of the line of people marching behind us. She stood up straighter and walked with even more conviction. We were both so proud of our fellow students.

We marched into the parking lot behind Morrison’s and as we came out around the corner toward the front of the building, there was a paddy wagon, and we were immediately arrested— told “John Doe or Jane Doe, you are under arrest.” Into the paddy wagon we went. On the way to jail our adrenaline levels were off the charts. We started introducing ourselves to each other in loud voices so the officers in the front could hear us. “Hi, I am John Doe.” “Well, I am Jane Doe. I wonder if we are related?” When we arrived at the jail, one of the police officers from the front was helping us out. As he assisted us, I heard him say, “I am sorry. I am just doing my job.”

We were taken in to be booked. This took some time as there were probably 20 or so of us to process. I was sitting on a radiator, next to the elevator. Since there weren’t enough places for everyone to sit, we rotated. Another guy took my place on the radiator and I sat in his place on a bench. A policeman saw him sitting on the radiator, came over, grabbed him by the scruff of his neck, and tossed him across the room, saying, “Were you trying to escape, boy?” The police had never touched me.

After being booked we were put in what we called “the hot room.” There were low wooden benches with hot spotlights shining down on us. We were left in there for several hours with no water. Some of us crawled under the benches on the cooler concrete floor.

We decided if, given the chance, we would stay in jail for the weekend. One by one we were called to a phone. I spoke with a man who told me that someone in New York was willing to post my bail if I wanted to get out right then. I thanked him but said we were staying in until Sunday. Our plan was to make Nashville pay for our room and board.

After several hours in custody we were taken to our cell. It had bunk beds for 12. There were 18 of us. There were no mattresses on the steel beds. The water had been turned off, including the toilet. Some of the guys had been in there for several days already. Ripe doesn’t begin to describe it! We had been searched before being put in the cell, but some of the guys had smuggled in some stuff. There were playing cards, reflector sunglasses, a belt, balloons—all sorts of stuff.

I remember men in the cell next to ours saying they would march with us if we could get them out. I remember our cell was in the corner above the fire station and that people came down and sang to us from the fire station parking lot. I remember it was hot and the guards had closed all of the exterior windows, but we became proficient at using the belt to lasso the casement window handles to open them. I remember running our metal cups up and down the bars. And I remember the juveniles in the cell behind us who kept yelling racial epithets in our direction. I don’t remember sleeping. I do remember the grits we were fed were very runny. On Sunday, the president of Fisk came to see us. Before he got there, mattresses had been brought in and the water was turned on.

We were told we would be getting out Sunday night but would have to be in court on Monday morning. Before leaving, we decided to get even with the juveniles next door. We hatched a plan. We filled up one of the balloons with water. Using the reflector sun glasses we could see down the hallway to their cell. One of the juveniles was particularly obnoxious. It was my job to get him mad—mad enough that he would put his face up against the bars yelling at me. I did my job. Another guy had the glasses tilted at the right angle and a third behind me had the water balloon. It worked to perfection. Direct hit. Cheers from the other juveniles!

On Sunday night I got back to the dorm. I immediately went to see my friend, Robert. Rather than being welcomed as a conquering hero, he told me what a fool I was. He told me I didn’t understand the danger I had put myself in. It was not the reaction I expected. I found out later that he had been involved in a demonstration before, had been surrounded by a hate-filled group of whites, and had been terrified. Besides, what had I really done?

I got back to my room and found under the door a letter from my mom. Air Mail Special Delivery. She said she was busting her buttons with pride, and it was the best Mother’s Day present she had ever gotten.

The next day we went to court. We were told by a couple of young black lawyers that our cases would be heard together. As we were talking, I heard my name called. It had been decided that the cases would be heard one at a time, starting with me. I was being charged with “Conspiracy to obstruct trade, commerce, and the administration of law.” As I was being briefed by the two lawyers on what to say and not say, I saw an elderly black man shuffle to the front of the courtroom. I couldn’t hear what was said but all of a sudden I heard “Case dismissed!”

It seems Morrison’s had had a restraining order taken out against the exchange student from Pomona and the police thought that was me. Plus it had been a John Doe warrant. I was free to go. All of the other students had their cases dismissed as well.

We learned that while we were in jail, students from Vanderbilt had showed up at Morrison’s just before church got out, a very busy time for the restaurant. The students and professors went in, sat down taking up most of the seats, and ordered coffee. They proceeded to drink the coffee for several hours, denying the use of the tables to those who wanted to order Sunday dinner.

I finished my semester at Fisk. I had learned what it was like, at least for a bit, to feel like a minority. I had learned about taking a stand. I had learned about friendship. I had learned about hate. I had learned a lot that could not be taught in a book. I found out that the summer after I left, Morrison’s Cafeteria integrated.