Built by design

Carefully planned, distinctively preserved, and now evolved for modern learning. Cornell’s ideal campus setting is a national treasure.

Many colleges founded before the Civil War—colleges like Cornell—shared assumptions about not only what should be taught but also where it should be taught. Learning required discipline and contemplation most easily achieved by limited isolation.

A college is a place of learning and meditation where all share in directed disciplined conversation. Close proximity is desirable and possible. Structures must be physically close, and in a walking culture the distance must remain short to encourage personal interaction. The buildings for living and learning were planned to enhance the sense of community that was at the heart of the experience of learning—the philosophical underpinnings for determining the best environment for learning.

Cornell retains this philosophy today as a residential liberal arts college.

For a college such as Cornell, founded by a Methodist minister, the ideal setting for learning is in the midst of a quiet place of beauty. It requires a vista as a constant reminder of the greatness of the creator and the generosity of the great maker of human cells, ants, and stars. A place where the learners know the power of the wind, the bitterness of the blizzard, as well as the unspeakable colors of autumn leaves—to experience the generosity of God and the strength beyond the self to endure climate shifts as well as conquer the pains of the heart.

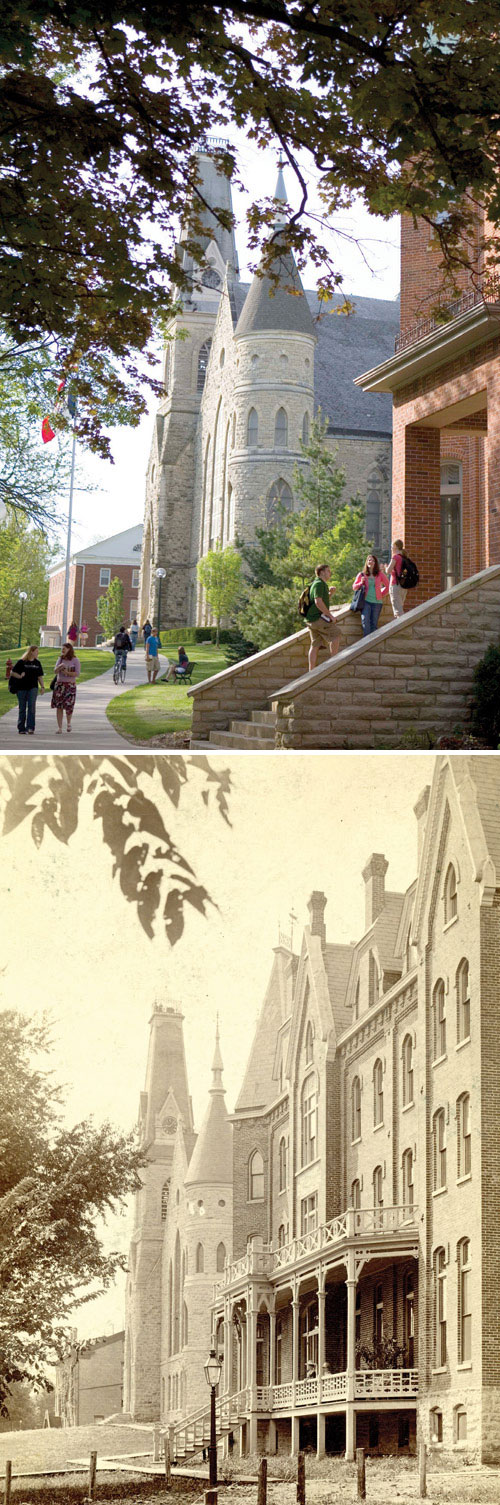

Indeed, the Cornell College campus has, since 1853, provided the vista, the beauty, and the extremes of seasons. In 1980 it deepened its commitment and showed its respect for the historic setting and buildings by becoming the first campus to be named in its entirety as a National Register District. During the current strategic planning process, the historic campus emerged as one of five themes of the upcoming strategic plan: “Enhancing a beautiful and well-purposed historic campus.”

The Rev. Bowman may have been the charismatic driver of the movement to build Cornell, but it was five or six forward-looking merchants who provided the capital to initiate the adventure and regular contributions to sustain it. None of the founders of this college had more than a few years of education, nor did they know how to run an academy. They did have faith in Bowman, God, and vision. They believed they were involved in accomplishing a sacred task—in addition to attracting educated persons who would provide leadership for civil life and bring students who stimulated commerce. (The college has maintained an affiliation with the United Methodist Church, and from the beginning has welcomed people from all religious traditions and from all non-religious perspectives.)

Intentional planning

Once the setting was secure the next task was to create structures for instruction and living facilities. Chance and opportunity joined with intention in campus planning. The reason for the placement of Old Sem is unknown but it is near the center of the original 20 acres of land at what was then the edge of town. The placement of College Hall to the east (towards the town) gives an early indication of plans to fill the east end of the campus. This is logical as the land to the west of Old Sem was a farmstead that blocked expansion in that direction. It would be later in the century when Cornell was able to purchase a large part of the land that allowed expansion.

In the West, before the Civil War, most new college buildings were adaptations of the popular Greek Revival style. The shape of the building and its limited exterior decoration was easily traced to the main lines of Greek architecture and design. What better style for a learning community than one that makes frequent visual reference to the Classical period that constituted the heart of the curriculum—emphasizing the role of the arts and the training of the mind in creating Western civilization? Cornell is no exception to this larger trend in college building.

Another feature of the early buildings on the campus is that they are “rooted” in their place by the materials used in their construction. The sand, water, and clay for the bricks are all locally available and together give the color of the brick a rather unique hue and color tone.

Thus the structures and the site form an organic union of nature and human creativity. The Cornell of the 19th century conformed to the assumptions that guided so many of the new colleges in the West. The addition of acres to the west provided the school with an opportunity to build along the ridge of hilltop.

By 1880 it was clear to trustees that the early decision to admit women as full members of the community was a solid financial decision. The rising number of women attending prompted the construction of a residence where women could enjoy their own community away from men. Bowman himself urged this adventure and raised considerable money to make it possible. The design of the building supported the popular notions of domesticity and encouraged the type of social etiquettes needed by women with a college degree destined to become community leaders. Bowman Hall is in essence a very large home (“domicile”) for the assumed needs of women.

At the 50th anniversary of the college (1903) the campus of five buildings and the spacious Ash Park celebrated its successful beginning and looked forward with confidence to the future. In the next 50 years the campus more than doubled in land area and buildings. At the centennial the campus extended from Fifth to 10th avenues and from First to Fourth streets southwest. Eleven major structures dotted the Hilltop along with some seven former homes that were in use and part of the campus property.

The campus and buildings conformed rather well to the cultural notions about the place for learning. With the coming of the 20th century, buildings designed for the use of only one or two academic disciplines appeared on campuses. That move was partly in response to the expansion in the number of academic disciplines created around the turn of the 20th century. College curriculums struggled to accommodate the growing influence of science and the scientific method. The gift of the Carnegie Library (1905) was clearly for one purpose. The Alumni Gymnasium (1909) was again a single purpose building and illustrates the growing interest in the proper use and development of the body as well as the rise of varsity sports.

By 1953 it was evident that the college was organized into three zones related to community life—each retaining the older importance of vistas and proximity of learners. The campus east of Old Sem had become the core of the academic buildings and activities. The chapel and library (the philosophic anchors of the enterprise) stand at the intersection of the academic area and the residents/service zone of the total campus, which extends to the western boundary. By the late 1950s the only academic building to violate this arrangement was Armstrong Hall (1938). The chapel from the ridge (mall) remained unobstructed to both the north and south. The chapel lawn remained wooded and without any structures—another key vista in the larger landscape. The dominance of the chapel on the larger landscape as well as the campus continued to have a rather dramatic effect on observers and again remind all that this enterprise is about something more than ourselves and our little world. King Chapel was a well-recognized symbol of the college and logo for both the town and school.

The first century of Cornell brought many changes in our landscape and in our perception of the natural and built environment. In retrospect the changes made during the second half of the 20th century seem far more dramatic than the previous half century.

Growth and modernization

The decision in 1961 to double the size of the college brought a modern and more secular vision of what should constitute a place for learning. The triumph of the secular humanist vision among intellectuals and the unlimited confidence in the new science to create a new and better world made the place of learning a new cathedral where the achievements of the human community were to be celebrated and worshiped. The older institutions found themselves as places with old structures that contributed little to the new knowledge and new science. The new urbanism had little time for places of meditation and urban sprawl made any plot of land a highly valuable economic commodity. Thus, the old intellectual foundations seemed swept away and large communities of learning took place in essentially crowded cities—universities became cities in themselves. The “action” was not in rural or small colleges but in the energy center of larger and more impersonal institutions that gave up attempts to be communities in any real sense.

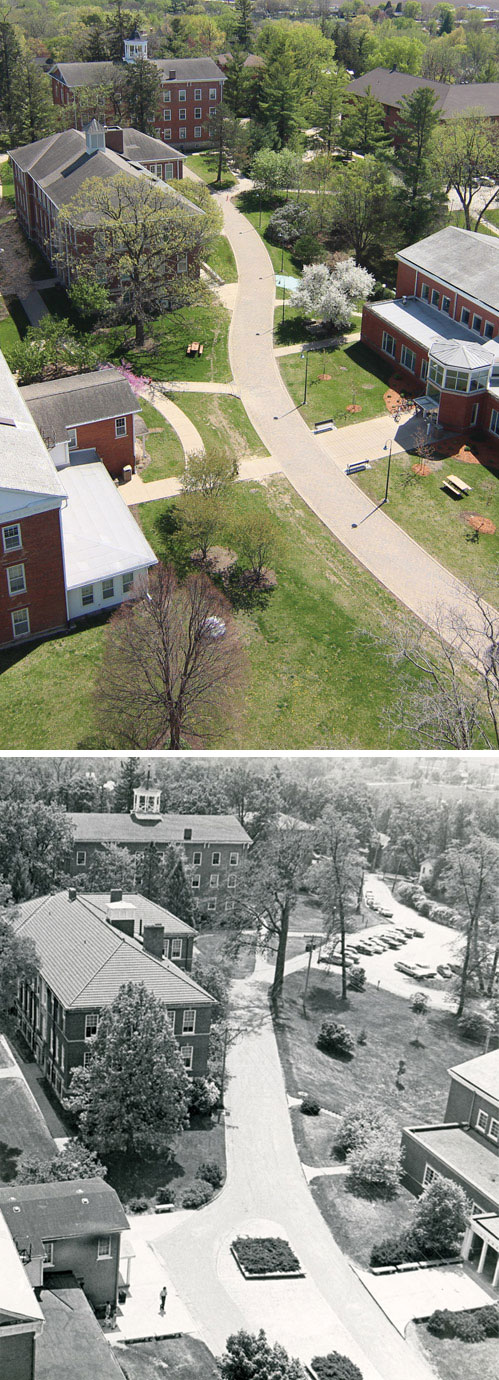

Cornell made the decision that, largely for economic reasons, the little school of 500 to 600 needed at least 1,000 tuition-paying students. With the improvement in auto and air travel, the market for new students had to be enlarged to include at least the Midwest region. Planners saw the campus property as large enough for the desired expansion. Between 1963 and 1967 the college built six new structures on the hilltop. They created two residence halls on Pfeiffer Hill (Dows and Tarr), making a small community of structures with an open courtyard and extraordinary vista—much in the spirit of the 19th century planners’ desire for social interactions that enhanced learning. They anchored the “student life zone” with a campus commons (1966) a short distance from all the residence halls. A second pair of residence halls on the west end of the campus property (Pauley and Rorem) brought that area into the student traffic patterns and enlarged the residence zone that had been limited to Olin and Merner halls. These buildings fit comfortably into the existing landscape without major damage to the traditional vistas.

The major visual change was the architectural style employed by Harry and Ben Weese. Five new buildings of a different architectural style dropped into a small area could easily overwhelm the older structures. But by a careful use of scale and minimal decoration on the cladding, together with a metal flashing along the top, the result is a good accommodation of the more horizontal lines of the entire campus.

Cornell has retained so much of the feel and inspiration of the 19th and 20th centuries because it conserved and respected its historic space and structures.

21st century changes

The three buildings in this new century reflect current perspectives about working with additions or companion structures to historic buildings. By placement and style the two new residence halls, New and Russell halls, do not detract from the artistic ambiance of the landscape. Youngker Hall (2002—seen below) has its own identity and integrity. It might become an in-law in the college family. It does not attempt to be a twin or a sibling to any of the campus family of buildings. While joined at the hip with Armstrong it expresses and celebrates an independence and freedom that is much in the modern spirit. It does so without insulting Armstrong. The two buildings are quite different in style yet appear to be respectful friends.

Not only has the institution recycled historic space for current needs (go green!) but also it has purchased and used more than 11 historic homes and integrated them into the campus. By carefully maintaining these properties the college has added to the historic ambiance of the town and aided in blending the town and college into one coherent community.

Perhaps the most interesting project from the point of view of the older cultural assumptions is the Marie Fletcher Carter Pedestrian Mall (2002). The old assumption about the importance of natural vista is affirmed and enhanced by this campus walk. It provides a restful opportunity as well as a delightful place for engaging conversation that often encourages learning as well as friendship. The campus was transformed by the removal of the distracting power-lines and poles that created an atmosphere of a back alley. A garden walk has replaced the alley and opens for us the possibility of slowing our pace and more easily sensing the beauty of this place of learning.

The proponents of the old assumption would applaud the Carter Pedestrian Mall and the older values that are still a part of the Cornell experience.

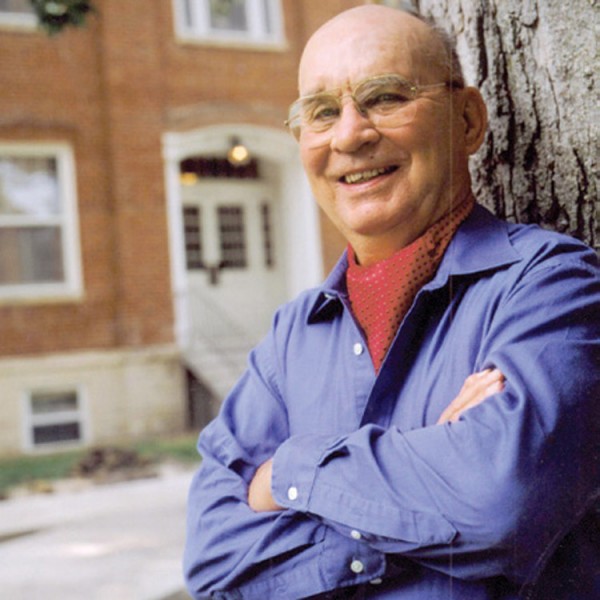

About the author

The Rev. Dr. Richard Thomas is Cornell College’s chaplain and professor emeritus of history. He is the author of Volume II of the college’s scholarly history, “Cornell College: A Sesquicentennial History,1853-2003” and the recipient of a Petersen/Harlan Award from the State Historical Society of Iowa, recognizing 40 years as an outstanding advocate for the study and appreciation of Iowa history. This reflection brings into focus years of study of the life of the college and the total built environment in which liberal education takes place.