The Joy of One Course At A Time

"What does the abbreviation 'Old Sem' stand for?" I asked. "Old Semester?" a student answered tentatively. Well. It has been 33 years since One Course At A Time replaced Cornell's semester system, which was before these students were born. For many of them, One Course At A Time was a major factor in their decision to attend Cornell. And while the nickname of the original campus building, Old Sem, is short for Iowa Conference Seminary (Cornell's name from 1853–1857), it is not hard to imagine how new students might connect this phrase with a different point in college history. Faculty voted for One Course At A Time in 1978, and since then have taught courses in intense three-and-a-half-week terms, followed by four-day block breaks. It is what makes Cornell nearly unique in higher education. And yet—as the saying goes—the more things change, the more they stay the same. In the end, One Course At A Time is a delivery method for the same rigorous liberal arts curriculum Cornell has offered for generations. Cornell alumni, pre- or post-One Course At A Time, experienced a transformational education. On the following pages are brief articles by six faculty members in divergent fields, describing how they teach differently because of the One Course At A Time calendar. The first article, by Professor Emeritus Richard Peterson, describes some of the similarities before and after One Course At A Time. In the end, he writes "One Course At A Time was another way to package what we had always done."One Course At A Time: Another approach to what we've always done

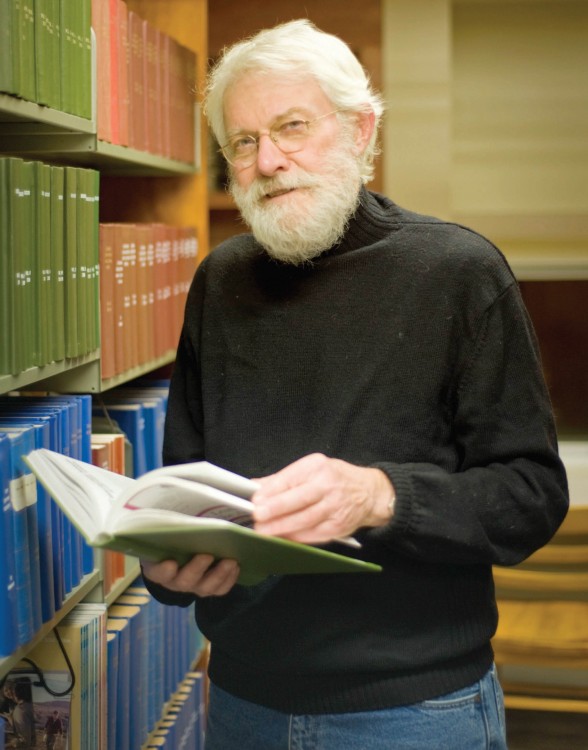

Richard Peterson, professor emeritus, sociology

[caption id="attachment_17323" align="alignnone" width="588"]

Richard Peterson (Photo by Mehrdad Zarifkar '09)[/caption]

1978 was a long time ago—34 years, to be exact. I had been teaching at Cornell for a few years and was finally learning what it meant to teach courses in this liberal arts context—the close interaction with students and with other disciplines, the insightful reading of texts, the thoughtful writing of essays, and the interplay of perspectives. The goal was to create ideas and actions that moved beyond a particular course. But then, right in the middle of my figuring this whole place out, the faculty adopted something called One Course At A Time. Now, why did we have to go and do a thing like that?

Once One Course At A Time was ushered in, the mad scramble to figure out how to work under this system began. How would we teach our courses? What kinds of texts could we read? What could we possibly ask our students to write in three-and-a-half weeks? We can't do all the things we used to do! That took weeks! Months! What will happen to the grand old tradition of the liberal arts? What will happen to academic rigor and integrity? We all scrambled about, pulling our individual and collective hair out. 1978 came and went. One Course At A Time happened—and it is still happening.

As I look back on all of this from the relative comfort of retirement, I see that much of the handwringing and head shaking was really not about change, but about continuity. The faculty saw—perhaps some more quickly than others—that One Course At A Time was another way to package what we had always done. One Course At A Time was not the compression of courses into a shorter period. Instead, it was taking what we had always done and figuring out how it might successfully be done in a shorter, more concentrated period of time. We found that we still assigned texts—books, scores, papers, experiences, what have you—but now we enjoyed the luxury of having extended, uninterrupted conversations about them. These deeper conversations about texts bring us closer to students and the students closer to the text. Writing, too, is still done as a central part of a Cornell education but is experienced differently. The same way time focuses reading and discussing, it also focuses writing. Instead of the long term paper, professors integrate writing and research throughout the block so that these become a habit of thinking rather than an end-of-term project. And, so we learned, we adapted, and we preserved the ideals we all admire and work toward.

My friend and colleague Charlotte Vaughan and I used to talk about the shift to One Course At A Time as the shift from skipping stones in a semester-long course to throwing rocks in the three-and-a-half week format. Stones skipping across the water skim the surface, while rocks thrown—carefully aimed—go into the water. The water is the same, the rocks are the same, but the thrown rocks go deeper. The ripples move outward, intersecting other ripples. And that, after all, is what the liberal arts has always been about.

Richard Peterson (Photo by Mehrdad Zarifkar '09)[/caption]

1978 was a long time ago—34 years, to be exact. I had been teaching at Cornell for a few years and was finally learning what it meant to teach courses in this liberal arts context—the close interaction with students and with other disciplines, the insightful reading of texts, the thoughtful writing of essays, and the interplay of perspectives. The goal was to create ideas and actions that moved beyond a particular course. But then, right in the middle of my figuring this whole place out, the faculty adopted something called One Course At A Time. Now, why did we have to go and do a thing like that?

Once One Course At A Time was ushered in, the mad scramble to figure out how to work under this system began. How would we teach our courses? What kinds of texts could we read? What could we possibly ask our students to write in three-and-a-half weeks? We can't do all the things we used to do! That took weeks! Months! What will happen to the grand old tradition of the liberal arts? What will happen to academic rigor and integrity? We all scrambled about, pulling our individual and collective hair out. 1978 came and went. One Course At A Time happened—and it is still happening.

As I look back on all of this from the relative comfort of retirement, I see that much of the handwringing and head shaking was really not about change, but about continuity. The faculty saw—perhaps some more quickly than others—that One Course At A Time was another way to package what we had always done. One Course At A Time was not the compression of courses into a shorter period. Instead, it was taking what we had always done and figuring out how it might successfully be done in a shorter, more concentrated period of time. We found that we still assigned texts—books, scores, papers, experiences, what have you—but now we enjoyed the luxury of having extended, uninterrupted conversations about them. These deeper conversations about texts bring us closer to students and the students closer to the text. Writing, too, is still done as a central part of a Cornell education but is experienced differently. The same way time focuses reading and discussing, it also focuses writing. Instead of the long term paper, professors integrate writing and research throughout the block so that these become a habit of thinking rather than an end-of-term project. And, so we learned, we adapted, and we preserved the ideals we all admire and work toward.

My friend and colleague Charlotte Vaughan and I used to talk about the shift to One Course At A Time as the shift from skipping stones in a semester-long course to throwing rocks in the three-and-a-half week format. Stones skipping across the water skim the surface, while rocks thrown—carefully aimed—go into the water. The water is the same, the rocks are the same, but the thrown rocks go deeper. The ripples move outward, intersecting other ripples. And that, after all, is what the liberal arts has always been about.

Can't imagine teaching on semesters again

David Yamanishi, associate professor of politics

[caption id="attachment_17324" align="alignnone" width="588"]

David Yamanishi (Photo by Aaron Hall '10)[/caption]

The advantages of the block plan are so many and so compelling that I can't imagine teaching on a semester or quarter plan again.

The block plan lets professors fit the class schedule to the needs of the class, rather than fit the needs of the class to the schedule. As a simple example, I start my Human Rights class with the film "Judgment at Nuremberg." On a traditional calendar, it would take almost two weeks worth of classes to watch the whole movie, during which my students (and possibly I) would forget why we were watching it. At Cornell, I can simply schedule a session long enough to watch it—or, if I'm feeling generous, with a break for lunch at the intermission.

As a more complicated example, even before starting at Cornell I thought it would be instructive to play the board game Diplomacy as a simulation in the basic international politics class. I now have groups of students play each country, and thus simulate the effects of various factors in the course of international relations. On a traditional calendar, I couldn't figure out how to do it. Even if I were blessed with a class an hour and 50 minutes long, we would only meet twice a week and we'd have to put everything else in the class on hold. Here at Cornell, we can have seminar meetings in the morning and do the simulation in the afternoons.

The community that the block plan makes of each class constantly amazes me. On any other calendar, students would be taking many classes at once and would naturally prioritize the work for the classes that matter most to them and have to divide their attention three or four ways. On the block plan, even in lower division classes, it's as if every class consists only of majors who have no other classes to dilute their attention.

Having only one class at a time has advantages off campus, too. Students can take internships or independent study blocks during the year. Political science students compete for summer internships in D.C., but at Cornell they can travel for one or two months during the academic year and have the opportunity to work on a special project rather than fight through the crowd of internship applicants during the industrial-scale summer internship process.

On a traditional plan, it's virtually impossible for a class to take a field trip. A class with 20 students might require the permission of up to 60 other instructors for a class to travel even for a day. Here at Cornell I've taken classes to the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art without having to make any special arrangements at all, because the trip can easily fit between 8 a.m. and 3 p.m. With the simple step of advance notice to the students, I will take my World War I-themed writing class on a day trip to the National World War I Museum in Kansas City later this year.

David Yamanishi (Photo by Aaron Hall '10)[/caption]

The advantages of the block plan are so many and so compelling that I can't imagine teaching on a semester or quarter plan again.

The block plan lets professors fit the class schedule to the needs of the class, rather than fit the needs of the class to the schedule. As a simple example, I start my Human Rights class with the film "Judgment at Nuremberg." On a traditional calendar, it would take almost two weeks worth of classes to watch the whole movie, during which my students (and possibly I) would forget why we were watching it. At Cornell, I can simply schedule a session long enough to watch it—or, if I'm feeling generous, with a break for lunch at the intermission.

As a more complicated example, even before starting at Cornell I thought it would be instructive to play the board game Diplomacy as a simulation in the basic international politics class. I now have groups of students play each country, and thus simulate the effects of various factors in the course of international relations. On a traditional calendar, I couldn't figure out how to do it. Even if I were blessed with a class an hour and 50 minutes long, we would only meet twice a week and we'd have to put everything else in the class on hold. Here at Cornell, we can have seminar meetings in the morning and do the simulation in the afternoons.

The community that the block plan makes of each class constantly amazes me. On any other calendar, students would be taking many classes at once and would naturally prioritize the work for the classes that matter most to them and have to divide their attention three or four ways. On the block plan, even in lower division classes, it's as if every class consists only of majors who have no other classes to dilute their attention.

Having only one class at a time has advantages off campus, too. Students can take internships or independent study blocks during the year. Political science students compete for summer internships in D.C., but at Cornell they can travel for one or two months during the academic year and have the opportunity to work on a special project rather than fight through the crowd of internship applicants during the industrial-scale summer internship process.

On a traditional plan, it's virtually impossible for a class to take a field trip. A class with 20 students might require the permission of up to 60 other instructors for a class to travel even for a day. Here at Cornell I've taken classes to the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art without having to make any special arrangements at all, because the trip can easily fit between 8 a.m. and 3 p.m. With the simple step of advance notice to the students, I will take my World War I-themed writing class on a day trip to the National World War I Museum in Kansas City later this year.

One Course At A Time ensures experiential learning

Melinda A. Green, associate professor of psychology

[caption id="attachment_17325" align="alignnone" width="659"]

Melinda Greene (Photo by Aaron Hall '10)[/caption]

Experiential-based learning activities abound at Cornell College, where One Course At A Time allows for classroom time to incorporate this type of teaching. On a traditional academic calendar, the professor may have 50 minutes three times per week to effectively teach a subject. At Cornell we have up to four hours per day to immerse students in one subject. Professors can use this time to teach the foundation of the material and then incorporate experiential learning exercises to reinforce the concepts. The learning and memory literature shows experiential learning leads to long-lasting memory traces. I feel privileged to teach on a schedule that allows me the flexibility to include many of these types of learning experiences.

For example, while learning about neural communication in my Biological Psychology course, students monitor their brain activity via electroencephalography. This exercise allows students to witness the changes in neural activity accompanying various behavior patterns. Students also study their cardiac reactions to various psychological states via the use of electrocardiography. In addition, students use electromyography to study skeletal muscle activation patterns in various behavioral states. Next, students get the opportunity to apply these research methodologies in their own original research proposals which are based on the existing primary literature in biological psychology and behavioral neuroscience.

The One Course At A Time calendar also allows students time to extend their learning beyond the classroom. For example, many of my brightest students seek out rigorous research opportunities in laboratories around the country via programs like Cornell Fellows. Unlike students attending institutions with a semester calendar, Cornell students can devote one or two months entirely to these research opportunities. This allows them to work alongside some of the leading researchers in the country. Students can experience what it's like to be a full-time research assistant in a nationally recognized laboratory, working to contribute to the knowledge base in an area about which they're passionate while honing their abilities. Cornell students return from these experiences with skills that inform their classroom perspectives as well as their professional aspirations.

Students also get the opportunity to conduct original research as they collaborate with their faculty mentors at Cornell. My research team in the department of psychology examines a variety of biological, psychological, and sociocultural predictors of eating disorders and body dissatisfaction. Each year I work closely with students to examine original research questions. We publish regularly in peer-reviewed journals and present at local, regional, and national conferences. Through these collaborations students gain the valuable skills necessary to excel in graduate and professional research. Many of my former students have secured professional research positions or have been accepted to graduate programs with a strong research component.

On a personal level, the close student-faculty relationships created by ongoing research collaborations frequently last far past graduation. Student-faculty research is one of my favorite activities because it allows me to provide the highest level of mentorship and forge lasting relationships with my students.

Melinda Greene (Photo by Aaron Hall '10)[/caption]

Experiential-based learning activities abound at Cornell College, where One Course At A Time allows for classroom time to incorporate this type of teaching. On a traditional academic calendar, the professor may have 50 minutes three times per week to effectively teach a subject. At Cornell we have up to four hours per day to immerse students in one subject. Professors can use this time to teach the foundation of the material and then incorporate experiential learning exercises to reinforce the concepts. The learning and memory literature shows experiential learning leads to long-lasting memory traces. I feel privileged to teach on a schedule that allows me the flexibility to include many of these types of learning experiences.

For example, while learning about neural communication in my Biological Psychology course, students monitor their brain activity via electroencephalography. This exercise allows students to witness the changes in neural activity accompanying various behavior patterns. Students also study their cardiac reactions to various psychological states via the use of electrocardiography. In addition, students use electromyography to study skeletal muscle activation patterns in various behavioral states. Next, students get the opportunity to apply these research methodologies in their own original research proposals which are based on the existing primary literature in biological psychology and behavioral neuroscience.

The One Course At A Time calendar also allows students time to extend their learning beyond the classroom. For example, many of my brightest students seek out rigorous research opportunities in laboratories around the country via programs like Cornell Fellows. Unlike students attending institutions with a semester calendar, Cornell students can devote one or two months entirely to these research opportunities. This allows them to work alongside some of the leading researchers in the country. Students can experience what it's like to be a full-time research assistant in a nationally recognized laboratory, working to contribute to the knowledge base in an area about which they're passionate while honing their abilities. Cornell students return from these experiences with skills that inform their classroom perspectives as well as their professional aspirations.

Students also get the opportunity to conduct original research as they collaborate with their faculty mentors at Cornell. My research team in the department of psychology examines a variety of biological, psychological, and sociocultural predictors of eating disorders and body dissatisfaction. Each year I work closely with students to examine original research questions. We publish regularly in peer-reviewed journals and present at local, regional, and national conferences. Through these collaborations students gain the valuable skills necessary to excel in graduate and professional research. Many of my former students have secured professional research positions or have been accepted to graduate programs with a strong research component.

On a personal level, the close student-faculty relationships created by ongoing research collaborations frequently last far past graduation. Student-faculty research is one of my favorite activities because it allows me to provide the highest level of mentorship and forge lasting relationships with my students.

Guest artists are the norm

Scott Olinger, associate professor of theatre

[caption id="attachment_17326" align="alignnone" width="591"]

Scott Olinger (Photo by Aaron Hall '10)[/caption]

I recently found myself (as I often do) sitting in a darkened and hushed backstage corridor, speaking with a producer. The academic year was set to begin in a few days, and I had extended the opportunity to work on a special off-campus project to a few students who were returning early to staff events during new student orientation. The producer had commented on the quality of the student work and asked, "I suppose it's not every day your students get to meet an Olympic gold medal winner and work with a Grammy award-winning producer, eh?" I grinned and replied, "Perhaps more often than you would think."

One of the things my colleagues and I appreciate most about One Course At A Time is the unprecedented access it allows to guest artists. Don't get me wrong; we're not interested in shopping out our teaching responsibilities, but we jump at the opportunity to expose our students to an array of professional artists from all corners of our field. In a traditional semester plan, you can certainly bring in a guest to meet with your class for a few hours over the course of a week, or perhaps schedule a master class on a weekend. But imagine a four-hour master class for several days, a week, or better yet, an entire block. Most theatre professionals are used to living their lives on six-week rehearsal periods before packing up and moving to the next show, and it's often not too difficult to squeeze in a three-and-a-half week residency in Mount Vernon with a little planning.

This approach has put our students in direct contact with professionals like David Apichell, the production stage manager at Madison Square Garden and touring stage manager for the Radio City Rockettes. It put actors onstage with David Combs, a member of the original Broadway cast of "Equus." Playwriting students are bouncing drafts off the likes of Naomi Wallace ("Lawn Dogs") and Keith Huff ("A Steady Rain"). And lighting designers are getting critical feedback from Stanley Crocker, touring designer for Sting and frequent designer for CMT's "Crossroads" and "Invitation Only" series.

And when we can't bring the artists here, the block plan allows us to go to them. It's not uncommon for my lighting design class to squeeze into a van and drive to Chicago to spend two hours with the production manager at the "Oprah Winfrey" show, or to tour the Electronic Theatre Controls plant in Madison with one of our two alumni employed there.

Could we do all of these things on a semester plan? Sure. You can make virtually anything happen if you work hard enough; isn't that what we want our students to believe? But if it's integral to the teaching approach rather than the exception, making it happen is the norm. It really is what you know that matters in the long run educationally, but who you know can really make a difference as well.

Scott Olinger (Photo by Aaron Hall '10)[/caption]

I recently found myself (as I often do) sitting in a darkened and hushed backstage corridor, speaking with a producer. The academic year was set to begin in a few days, and I had extended the opportunity to work on a special off-campus project to a few students who were returning early to staff events during new student orientation. The producer had commented on the quality of the student work and asked, "I suppose it's not every day your students get to meet an Olympic gold medal winner and work with a Grammy award-winning producer, eh?" I grinned and replied, "Perhaps more often than you would think."

One of the things my colleagues and I appreciate most about One Course At A Time is the unprecedented access it allows to guest artists. Don't get me wrong; we're not interested in shopping out our teaching responsibilities, but we jump at the opportunity to expose our students to an array of professional artists from all corners of our field. In a traditional semester plan, you can certainly bring in a guest to meet with your class for a few hours over the course of a week, or perhaps schedule a master class on a weekend. But imagine a four-hour master class for several days, a week, or better yet, an entire block. Most theatre professionals are used to living their lives on six-week rehearsal periods before packing up and moving to the next show, and it's often not too difficult to squeeze in a three-and-a-half week residency in Mount Vernon with a little planning.

This approach has put our students in direct contact with professionals like David Apichell, the production stage manager at Madison Square Garden and touring stage manager for the Radio City Rockettes. It put actors onstage with David Combs, a member of the original Broadway cast of "Equus." Playwriting students are bouncing drafts off the likes of Naomi Wallace ("Lawn Dogs") and Keith Huff ("A Steady Rain"). And lighting designers are getting critical feedback from Stanley Crocker, touring designer for Sting and frequent designer for CMT's "Crossroads" and "Invitation Only" series.

And when we can't bring the artists here, the block plan allows us to go to them. It's not uncommon for my lighting design class to squeeze into a van and drive to Chicago to spend two hours with the production manager at the "Oprah Winfrey" show, or to tour the Electronic Theatre Controls plant in Madison with one of our two alumni employed there.

Could we do all of these things on a semester plan? Sure. You can make virtually anything happen if you work hard enough; isn't that what we want our students to believe? But if it's integral to the teaching approach rather than the exception, making it happen is the norm. It really is what you know that matters in the long run educationally, but who you know can really make a difference as well.

One Course At A Time intensity fosters language learning

Devan Baty, associate professor of French

[caption id="attachment_17327" align="alignnone" width="573"]

Devan Baty (Photo by Aaron Hall '10)[/caption]

Learning a foreign language is a transformative experience. With each new word and expression, you see and experience the world in new ways. From the first day of French 101, you abandon your comfort zone. No longer a mere spectator or tourist, you become a direct participant in the global Francophone community by engaging with it on its own terms and in its own words.

The intensity of the block plan fosters a sense of community, which begins in the classroom. Students learn about each other and themselves while they are learning about French and Francophone culture. They not only study the form of the language, they also learn about the cultural contexts in which the language is spoken and lived. For example, a typical day's lesson in a language class under One Course At A Time includes a variety of activities, which build upon each other throughout the day. When learning about education, for example, students in Intermediate French begin by putting into practice new vocabulary and grammar to describe their own experiences at college. This is followed by a discussion of the differences between American and French educational systems and their impact on culture and national identity. Language students are most engaged when their learning is placed into a broader context. We bring that context to the classroom with culturally rich materials such as music, film, art, food, and literature.

The flexibility of One Course At A Time also allows me to take students off campus on short trips to neighboring towns to take advantage of opportunities to learn more about the world where French is spoken. I have taken students to visit an exhibition of Haitian art at the Figge Museum in Davenport, Iowa; to attend a lecture in Iowa City by Angélique Kidjo, a United Nations spokeswoman for child rights in Africa; and to sample pains au chocolat at a traditional French café in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Croissant Du Jour. I have also hosted students at my home for a traditional dîner gastronomique with multiple courses and conversation in French.

Since we can't leave the Hilltop every day to discover the wider Francophone world, I invite French speakers to join our community as frequently as possible. For example, students in an advanced-level course on French and Francophone culture had the opportunity to learn about the difficulties of cultural integration from a group of Congolese immigrants who visited our class from their new home in Cedar Rapids. Other class visitors have included native French speakers from Togo, France, Québec, and Luxembourg.

One Course At A Time has also inspired me to lead off-campus courses in locations such as Montréal, Canada; Fez, Morocco; and Aix-en-Provence, France. In a month's time, students make great strides in their speaking and listening skills by living with host families and engaging with local communities in French. Their cultural proficiency improves even more as they are forced to navigate the unspoken codes and customs of the society in which they are placed.

In the words of one of my French students: "Vive l'One Course At A Time!"

Devan Baty (Photo by Aaron Hall '10)[/caption]

Learning a foreign language is a transformative experience. With each new word and expression, you see and experience the world in new ways. From the first day of French 101, you abandon your comfort zone. No longer a mere spectator or tourist, you become a direct participant in the global Francophone community by engaging with it on its own terms and in its own words.

The intensity of the block plan fosters a sense of community, which begins in the classroom. Students learn about each other and themselves while they are learning about French and Francophone culture. They not only study the form of the language, they also learn about the cultural contexts in which the language is spoken and lived. For example, a typical day's lesson in a language class under One Course At A Time includes a variety of activities, which build upon each other throughout the day. When learning about education, for example, students in Intermediate French begin by putting into practice new vocabulary and grammar to describe their own experiences at college. This is followed by a discussion of the differences between American and French educational systems and their impact on culture and national identity. Language students are most engaged when their learning is placed into a broader context. We bring that context to the classroom with culturally rich materials such as music, film, art, food, and literature.

The flexibility of One Course At A Time also allows me to take students off campus on short trips to neighboring towns to take advantage of opportunities to learn more about the world where French is spoken. I have taken students to visit an exhibition of Haitian art at the Figge Museum in Davenport, Iowa; to attend a lecture in Iowa City by Angélique Kidjo, a United Nations spokeswoman for child rights in Africa; and to sample pains au chocolat at a traditional French café in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Croissant Du Jour. I have also hosted students at my home for a traditional dîner gastronomique with multiple courses and conversation in French.

Since we can't leave the Hilltop every day to discover the wider Francophone world, I invite French speakers to join our community as frequently as possible. For example, students in an advanced-level course on French and Francophone culture had the opportunity to learn about the difficulties of cultural integration from a group of Congolese immigrants who visited our class from their new home in Cedar Rapids. Other class visitors have included native French speakers from Togo, France, Québec, and Luxembourg.

One Course At A Time has also inspired me to lead off-campus courses in locations such as Montréal, Canada; Fez, Morocco; and Aix-en-Provence, France. In a month's time, students make great strides in their speaking and listening skills by living with host families and engaging with local communities in French. Their cultural proficiency improves even more as they are forced to navigate the unspoken codes and customs of the society in which they are placed.

In the words of one of my French students: "Vive l'One Course At A Time!"

One Course At A Time is ideal for field trips, research

Emily Walsh, associate professor of geology

[caption id="attachment_17328" align="alignnone" width="729"]

Emily Walsh (Photo by Aaron Hall '10)[/caption]

I love to tell my colleagues at other schools about the One Course At A Time system at Cornell. Often they are skeptical about teaching and learning on such a short calendar, but as I answer them, I get increasingly excited about all the positive aspects of the One Course At A Time system. For teaching geology, this might just be the ideal college schedule.

Why? The freedom of long class periods and the lack of other academic priorities for the students. The best place to learn about geology is in the field or in the lab where students can interact with the Earth, and with One Course At A Time I have the flexibility to take students out of the classroom. Even the most difficult concepts become clearer when you can stare at the rock, touch it, sketch it, follow it through the woods, hammer it, and examine it at length with a hand lens. As long as the field trips are in the syllabus at the start of class, I can schedule field trips of any length, ranging from half a day to several weeks.

Almost every geology course on the books at Cornell has a major field or lab component—even the introductory courses include several all-day field trips, and some are based around a series of field-based labs with little lecture involved. Majors are required to take at least one field course (the full block is spent in the field), and most of the upper-level courses include at least a weekend field trip. The first time I taught Igneous and Metamorphic Petrology, we (the professor included) were so exhausted by the end of three weeks that we decided to jump into a van and drive to southern Missouri to see the rocks in the field. No other system would enable such a spontaneous excursion. Since then, that three-day field trip has been part of the course syllabus.

Field trips benefit nearly every Cornell student who takes a geology course, but geology majors get the added benefit of research blocks. Every geology major at Cornell must complete at least one block of independent research; those who go on to graduate school after Cornell (a significant number) find out that a research block is the perfect way to prepare for the intensity and freedom of a graduate research schedule. Performing research during a block requires self-motivation as well as self-discipline; while the students have regular meetings with their faculty mentor and other students in the research group, the majority of their time is spent reading the literature, writing proposals and papers, performing research, and interpreting data. Any student who has completed such a research block understands the necessity for self-motivation and self-discipline in graduate school and has the tools to succeed.

At this point I may pause to take a breath, but I have already convinced my colleagues. They all wish they taught on the One Course At A Time system, too, and I realize again how fortunate I am to be teaching at Cornell College."

["post_title"]=>

string(31) "The Joy of One Course At A Time"

["post_excerpt"]=>

string(184) "During a New Student Orientation activity last fall, small groups of first-year students answered trivia questions on their way downtown for a community event called Viva Mount Vernon."

["post_status"]=>

string(7) "publish"

["comment_status"]=>

string(6) "closed"

["ping_status"]=>

string(6) "closed"

["post_password"]=>

string(0) ""

["post_name"]=>

string(31) "the-joy-of-one-course-at-a-time"

["to_ping"]=>

string(0) ""

["pinged"]=>

string(0) ""

["post_modified"]=>

string(19) "2022-08-30 10:46:42"

["post_modified_gmt"]=>

string(19) "2022-08-30 15:46:42"

["post_content_filtered"]=>

string(23046) "

Emily Walsh (Photo by Aaron Hall '10)[/caption]

I love to tell my colleagues at other schools about the One Course At A Time system at Cornell. Often they are skeptical about teaching and learning on such a short calendar, but as I answer them, I get increasingly excited about all the positive aspects of the One Course At A Time system. For teaching geology, this might just be the ideal college schedule.

Why? The freedom of long class periods and the lack of other academic priorities for the students. The best place to learn about geology is in the field or in the lab where students can interact with the Earth, and with One Course At A Time I have the flexibility to take students out of the classroom. Even the most difficult concepts become clearer when you can stare at the rock, touch it, sketch it, follow it through the woods, hammer it, and examine it at length with a hand lens. As long as the field trips are in the syllabus at the start of class, I can schedule field trips of any length, ranging from half a day to several weeks.

Almost every geology course on the books at Cornell has a major field or lab component—even the introductory courses include several all-day field trips, and some are based around a series of field-based labs with little lecture involved. Majors are required to take at least one field course (the full block is spent in the field), and most of the upper-level courses include at least a weekend field trip. The first time I taught Igneous and Metamorphic Petrology, we (the professor included) were so exhausted by the end of three weeks that we decided to jump into a van and drive to southern Missouri to see the rocks in the field. No other system would enable such a spontaneous excursion. Since then, that three-day field trip has been part of the course syllabus.

Field trips benefit nearly every Cornell student who takes a geology course, but geology majors get the added benefit of research blocks. Every geology major at Cornell must complete at least one block of independent research; those who go on to graduate school after Cornell (a significant number) find out that a research block is the perfect way to prepare for the intensity and freedom of a graduate research schedule. Performing research during a block requires self-motivation as well as self-discipline; while the students have regular meetings with their faculty mentor and other students in the research group, the majority of their time is spent reading the literature, writing proposals and papers, performing research, and interpreting data. Any student who has completed such a research block understands the necessity for self-motivation and self-discipline in graduate school and has the tools to succeed.

At this point I may pause to take a breath, but I have already convinced my colleagues. They all wish they taught on the One Course At A Time system, too, and I realize again how fortunate I am to be teaching at Cornell College."

["post_title"]=>

string(31) "The Joy of One Course At A Time"

["post_excerpt"]=>

string(184) "During a New Student Orientation activity last fall, small groups of first-year students answered trivia questions on their way downtown for a community event called Viva Mount Vernon."

["post_status"]=>

string(7) "publish"

["comment_status"]=>

string(6) "closed"

["ping_status"]=>

string(6) "closed"

["post_password"]=>

string(0) ""

["post_name"]=>

string(31) "the-joy-of-one-course-at-a-time"

["to_ping"]=>

string(0) ""

["pinged"]=>

string(0) ""

["post_modified"]=>

string(19) "2022-08-30 10:46:42"

["post_modified_gmt"]=>

string(19) "2022-08-30 15:46:42"

["post_content_filtered"]=>

string(23046) " During a New Student Orientation activity last fall, small groups of first-year students answered trivia questions on their way downtown for a community event called Viva Mount Vernon. One response made me smile.

"What does the abbreviation 'Old Sem' stand for?" I asked.

"Old Semester?" a student answered tentatively.

Well. It has been 33 years since One Course At A Time replaced Cornell's semester system, which was before these students were born. For many of them, One Course At A Time was a major factor in their decision to attend Cornell. And while the nickname of the original campus building, Old Sem, is short for Iowa Conference Seminary (Cornell's name from 1853–1857), it is not hard to imagine how new students might connect this phrase with a different point in college history.

Faculty voted for One Course At A Time in 1978, and since then have taught courses in intense three-and-a-half-week terms, followed by four-day block breaks. It is what makes Cornell nearly unique in higher education.

And yet—as the saying goes—the more things change, the more they stay the same. In the end, One Course At A Time is a delivery method for the same rigorous liberal arts curriculum Cornell has offered for generations. Cornell alumni, pre- or post-One Course At A Time, experienced a transformational education.

On the following pages are brief articles by six faculty members in divergent fields, describing how they teach differently because of the One Course At A Time calendar. The first article, by Professor Emeritus Richard Peterson, describes some of the similarities before and after One Course At A Time. In the end, he writes "One Course At A Time was another way to package what we had always done."

During a New Student Orientation activity last fall, small groups of first-year students answered trivia questions on their way downtown for a community event called Viva Mount Vernon. One response made me smile.

"What does the abbreviation 'Old Sem' stand for?" I asked.

"Old Semester?" a student answered tentatively.

Well. It has been 33 years since One Course At A Time replaced Cornell's semester system, which was before these students were born. For many of them, One Course At A Time was a major factor in their decision to attend Cornell. And while the nickname of the original campus building, Old Sem, is short for Iowa Conference Seminary (Cornell's name from 1853–1857), it is not hard to imagine how new students might connect this phrase with a different point in college history.

Faculty voted for One Course At A Time in 1978, and since then have taught courses in intense three-and-a-half-week terms, followed by four-day block breaks. It is what makes Cornell nearly unique in higher education.

And yet—as the saying goes—the more things change, the more they stay the same. In the end, One Course At A Time is a delivery method for the same rigorous liberal arts curriculum Cornell has offered for generations. Cornell alumni, pre- or post-One Course At A Time, experienced a transformational education.

On the following pages are brief articles by six faculty members in divergent fields, describing how they teach differently because of the One Course At A Time calendar. The first article, by Professor Emeritus Richard Peterson, describes some of the similarities before and after One Course At A Time. In the end, he writes "One Course At A Time was another way to package what we had always done."

One Course At A Time: Another approach to what we've always done

Richard Peterson, professor emeritus, sociology

[caption id="attachment_17323" align="alignnone" width="588"]

Richard Peterson (Photo by Mehrdad Zarifkar '09)[/caption]

1978 was a long time ago—34 years, to be exact. I had been teaching at Cornell for a few years and was finally learning what it meant to teach courses in this liberal arts context—the close interaction with students and with other disciplines, the insightful reading of texts, the thoughtful writing of essays, and the interplay of perspectives. The goal was to create ideas and actions that moved beyond a particular course. But then, right in the middle of my figuring this whole place out, the faculty adopted something called One Course At A Time. Now, why did we have to go and do a thing like that?

Once One Course At A Time was ushered in, the mad scramble to figure out how to work under this system began. How would we teach our courses? What kinds of texts could we read? What could we possibly ask our students to write in three-and-a-half weeks? We can't do all the things we used to do! That took weeks! Months! What will happen to the grand old tradition of the liberal arts? What will happen to academic rigor and integrity? We all scrambled about, pulling our individual and collective hair out. 1978 came and went. One Course At A Time happened—and it is still happening.

As I look back on all of this from the relative comfort of retirement, I see that much of the handwringing and head shaking was really not about change, but about continuity. The faculty saw—perhaps some more quickly than others—that One Course At A Time was another way to package what we had always done. One Course At A Time was not the compression of courses into a shorter period. Instead, it was taking what we had always done and figuring out how it might successfully be done in a shorter, more concentrated period of time. We found that we still assigned texts—books, scores, papers, experiences, what have you—but now we enjoyed the luxury of having extended, uninterrupted conversations about them. These deeper conversations about texts bring us closer to students and the students closer to the text. Writing, too, is still done as a central part of a Cornell education but is experienced differently. The same way time focuses reading and discussing, it also focuses writing. Instead of the long term paper, professors integrate writing and research throughout the block so that these become a habit of thinking rather than an end-of-term project. And, so we learned, we adapted, and we preserved the ideals we all admire and work toward.

My friend and colleague Charlotte Vaughan and I used to talk about the shift to One Course At A Time as the shift from skipping stones in a semester-long course to throwing rocks in the three-and-a-half week format. Stones skipping across the water skim the surface, while rocks thrown—carefully aimed—go into the water. The water is the same, the rocks are the same, but the thrown rocks go deeper. The ripples move outward, intersecting other ripples. And that, after all, is what the liberal arts has always been about.

Richard Peterson (Photo by Mehrdad Zarifkar '09)[/caption]

1978 was a long time ago—34 years, to be exact. I had been teaching at Cornell for a few years and was finally learning what it meant to teach courses in this liberal arts context—the close interaction with students and with other disciplines, the insightful reading of texts, the thoughtful writing of essays, and the interplay of perspectives. The goal was to create ideas and actions that moved beyond a particular course. But then, right in the middle of my figuring this whole place out, the faculty adopted something called One Course At A Time. Now, why did we have to go and do a thing like that?

Once One Course At A Time was ushered in, the mad scramble to figure out how to work under this system began. How would we teach our courses? What kinds of texts could we read? What could we possibly ask our students to write in three-and-a-half weeks? We can't do all the things we used to do! That took weeks! Months! What will happen to the grand old tradition of the liberal arts? What will happen to academic rigor and integrity? We all scrambled about, pulling our individual and collective hair out. 1978 came and went. One Course At A Time happened—and it is still happening.

As I look back on all of this from the relative comfort of retirement, I see that much of the handwringing and head shaking was really not about change, but about continuity. The faculty saw—perhaps some more quickly than others—that One Course At A Time was another way to package what we had always done. One Course At A Time was not the compression of courses into a shorter period. Instead, it was taking what we had always done and figuring out how it might successfully be done in a shorter, more concentrated period of time. We found that we still assigned texts—books, scores, papers, experiences, what have you—but now we enjoyed the luxury of having extended, uninterrupted conversations about them. These deeper conversations about texts bring us closer to students and the students closer to the text. Writing, too, is still done as a central part of a Cornell education but is experienced differently. The same way time focuses reading and discussing, it also focuses writing. Instead of the long term paper, professors integrate writing and research throughout the block so that these become a habit of thinking rather than an end-of-term project. And, so we learned, we adapted, and we preserved the ideals we all admire and work toward.

My friend and colleague Charlotte Vaughan and I used to talk about the shift to One Course At A Time as the shift from skipping stones in a semester-long course to throwing rocks in the three-and-a-half week format. Stones skipping across the water skim the surface, while rocks thrown—carefully aimed—go into the water. The water is the same, the rocks are the same, but the thrown rocks go deeper. The ripples move outward, intersecting other ripples. And that, after all, is what the liberal arts has always been about.

Can't imagine teaching on semesters again

David Yamanishi, associate professor of politics

[caption id="attachment_17324" align="alignnone" width="588"]

David Yamanishi (Photo by Aaron Hall '10)[/caption]

The advantages of the block plan are so many and so compelling that I can't imagine teaching on a semester or quarter plan again.

The block plan lets professors fit the class schedule to the needs of the class, rather than fit the needs of the class to the schedule. As a simple example, I start my Human Rights class with the film "Judgment at Nuremberg." On a traditional calendar, it would take almost two weeks worth of classes to watch the whole movie, during which my students (and possibly I) would forget why we were watching it. At Cornell, I can simply schedule a session long enough to watch it—or, if I'm feeling generous, with a break for lunch at the intermission.

As a more complicated example, even before starting at Cornell I thought it would be instructive to play the board game Diplomacy as a simulation in the basic international politics class. I now have groups of students play each country, and thus simulate the effects of various factors in the course of international relations. On a traditional calendar, I couldn't figure out how to do it. Even if I were blessed with a class an hour and 50 minutes long, we would only meet twice a week and we'd have to put everything else in the class on hold. Here at Cornell, we can have seminar meetings in the morning and do the simulation in the afternoons.

The community that the block plan makes of each class constantly amazes me. On any other calendar, students would be taking many classes at once and would naturally prioritize the work for the classes that matter most to them and have to divide their attention three or four ways. On the block plan, even in lower division classes, it's as if every class consists only of majors who have no other classes to dilute their attention.

Having only one class at a time has advantages off campus, too. Students can take internships or independent study blocks during the year. Political science students compete for summer internships in D.C., but at Cornell they can travel for one or two months during the academic year and have the opportunity to work on a special project rather than fight through the crowd of internship applicants during the industrial-scale summer internship process.

On a traditional plan, it's virtually impossible for a class to take a field trip. A class with 20 students might require the permission of up to 60 other instructors for a class to travel even for a day. Here at Cornell I've taken classes to the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art without having to make any special arrangements at all, because the trip can easily fit between 8 a.m. and 3 p.m. With the simple step of advance notice to the students, I will take my World War I-themed writing class on a day trip to the National World War I Museum in Kansas City later this year.

David Yamanishi (Photo by Aaron Hall '10)[/caption]

The advantages of the block plan are so many and so compelling that I can't imagine teaching on a semester or quarter plan again.

The block plan lets professors fit the class schedule to the needs of the class, rather than fit the needs of the class to the schedule. As a simple example, I start my Human Rights class with the film "Judgment at Nuremberg." On a traditional calendar, it would take almost two weeks worth of classes to watch the whole movie, during which my students (and possibly I) would forget why we were watching it. At Cornell, I can simply schedule a session long enough to watch it—or, if I'm feeling generous, with a break for lunch at the intermission.

As a more complicated example, even before starting at Cornell I thought it would be instructive to play the board game Diplomacy as a simulation in the basic international politics class. I now have groups of students play each country, and thus simulate the effects of various factors in the course of international relations. On a traditional calendar, I couldn't figure out how to do it. Even if I were blessed with a class an hour and 50 minutes long, we would only meet twice a week and we'd have to put everything else in the class on hold. Here at Cornell, we can have seminar meetings in the morning and do the simulation in the afternoons.

The community that the block plan makes of each class constantly amazes me. On any other calendar, students would be taking many classes at once and would naturally prioritize the work for the classes that matter most to them and have to divide their attention three or four ways. On the block plan, even in lower division classes, it's as if every class consists only of majors who have no other classes to dilute their attention.

Having only one class at a time has advantages off campus, too. Students can take internships or independent study blocks during the year. Political science students compete for summer internships in D.C., but at Cornell they can travel for one or two months during the academic year and have the opportunity to work on a special project rather than fight through the crowd of internship applicants during the industrial-scale summer internship process.

On a traditional plan, it's virtually impossible for a class to take a field trip. A class with 20 students might require the permission of up to 60 other instructors for a class to travel even for a day. Here at Cornell I've taken classes to the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art without having to make any special arrangements at all, because the trip can easily fit between 8 a.m. and 3 p.m. With the simple step of advance notice to the students, I will take my World War I-themed writing class on a day trip to the National World War I Museum in Kansas City later this year.

One Course At A Time ensures experiential learning

Melinda A. Green, associate professor of psychology

[caption id="attachment_17325" align="alignnone" width="659"]

Melinda Greene (Photo by Aaron Hall '10)[/caption]

Experiential-based learning activities abound at Cornell College, where One Course At A Time allows for classroom time to incorporate this type of teaching. On a traditional academic calendar, the professor may have 50 minutes three times per week to effectively teach a subject. At Cornell we have up to four hours per day to immerse students in one subject. Professors can use this time to teach the foundation of the material and then incorporate experiential learning exercises to reinforce the concepts. The learning and memory literature shows experiential learning leads to long-lasting memory traces. I feel privileged to teach on a schedule that allows me the flexibility to include many of these types of learning experiences.

For example, while learning about neural communication in my Biological Psychology course, students monitor their brain activity via electroencephalography. This exercise allows students to witness the changes in neural activity accompanying various behavior patterns. Students also study their cardiac reactions to various psychological states via the use of electrocardiography. In addition, students use electromyography to study skeletal muscle activation patterns in various behavioral states. Next, students get the opportunity to apply these research methodologies in their own original research proposals which are based on the existing primary literature in biological psychology and behavioral neuroscience.

The One Course At A Time calendar also allows students time to extend their learning beyond the classroom. For example, many of my brightest students seek out rigorous research opportunities in laboratories around the country via programs like Cornell Fellows. Unlike students attending institutions with a semester calendar, Cornell students can devote one or two months entirely to these research opportunities. This allows them to work alongside some of the leading researchers in the country. Students can experience what it's like to be a full-time research assistant in a nationally recognized laboratory, working to contribute to the knowledge base in an area about which they're passionate while honing their abilities. Cornell students return from these experiences with skills that inform their classroom perspectives as well as their professional aspirations.

Students also get the opportunity to conduct original research as they collaborate with their faculty mentors at Cornell. My research team in the department of psychology examines a variety of biological, psychological, and sociocultural predictors of eating disorders and body dissatisfaction. Each year I work closely with students to examine original research questions. We publish regularly in peer-reviewed journals and present at local, regional, and national conferences. Through these collaborations students gain the valuable skills necessary to excel in graduate and professional research. Many of my former students have secured professional research positions or have been accepted to graduate programs with a strong research component.

On a personal level, the close student-faculty relationships created by ongoing research collaborations frequently last far past graduation. Student-faculty research is one of my favorite activities because it allows me to provide the highest level of mentorship and forge lasting relationships with my students.

Melinda Greene (Photo by Aaron Hall '10)[/caption]

Experiential-based learning activities abound at Cornell College, where One Course At A Time allows for classroom time to incorporate this type of teaching. On a traditional academic calendar, the professor may have 50 minutes three times per week to effectively teach a subject. At Cornell we have up to four hours per day to immerse students in one subject. Professors can use this time to teach the foundation of the material and then incorporate experiential learning exercises to reinforce the concepts. The learning and memory literature shows experiential learning leads to long-lasting memory traces. I feel privileged to teach on a schedule that allows me the flexibility to include many of these types of learning experiences.

For example, while learning about neural communication in my Biological Psychology course, students monitor their brain activity via electroencephalography. This exercise allows students to witness the changes in neural activity accompanying various behavior patterns. Students also study their cardiac reactions to various psychological states via the use of electrocardiography. In addition, students use electromyography to study skeletal muscle activation patterns in various behavioral states. Next, students get the opportunity to apply these research methodologies in their own original research proposals which are based on the existing primary literature in biological psychology and behavioral neuroscience.

The One Course At A Time calendar also allows students time to extend their learning beyond the classroom. For example, many of my brightest students seek out rigorous research opportunities in laboratories around the country via programs like Cornell Fellows. Unlike students attending institutions with a semester calendar, Cornell students can devote one or two months entirely to these research opportunities. This allows them to work alongside some of the leading researchers in the country. Students can experience what it's like to be a full-time research assistant in a nationally recognized laboratory, working to contribute to the knowledge base in an area about which they're passionate while honing their abilities. Cornell students return from these experiences with skills that inform their classroom perspectives as well as their professional aspirations.

Students also get the opportunity to conduct original research as they collaborate with their faculty mentors at Cornell. My research team in the department of psychology examines a variety of biological, psychological, and sociocultural predictors of eating disorders and body dissatisfaction. Each year I work closely with students to examine original research questions. We publish regularly in peer-reviewed journals and present at local, regional, and national conferences. Through these collaborations students gain the valuable skills necessary to excel in graduate and professional research. Many of my former students have secured professional research positions or have been accepted to graduate programs with a strong research component.

On a personal level, the close student-faculty relationships created by ongoing research collaborations frequently last far past graduation. Student-faculty research is one of my favorite activities because it allows me to provide the highest level of mentorship and forge lasting relationships with my students.

Guest artists are the norm

Scott Olinger, associate professor of theatre

[caption id="attachment_17326" align="alignnone" width="591"]

Scott Olinger (Photo by Aaron Hall '10)[/caption]

I recently found myself (as I often do) sitting in a darkened and hushed backstage corridor, speaking with a producer. The academic year was set to begin in a few days, and I had extended the opportunity to work on a special off-campus project to a few students who were returning early to staff events during new student orientation. The producer had commented on the quality of the student work and asked, "I suppose it's not every day your students get to meet an Olympic gold medal winner and work with a Grammy award-winning producer, eh?" I grinned and replied, "Perhaps more often than you would think."

One of the things my colleagues and I appreciate most about One Course At A Time is the unprecedented access it allows to guest artists. Don't get me wrong; we're not interested in shopping out our teaching responsibilities, but we jump at the opportunity to expose our students to an array of professional artists from all corners of our field. In a traditional semester plan, you can certainly bring in a guest to meet with your class for a few hours over the course of a week, or perhaps schedule a master class on a weekend. But imagine a four-hour master class for several days, a week, or better yet, an entire block. Most theatre professionals are used to living their lives on six-week rehearsal periods before packing up and moving to the next show, and it's often not too difficult to squeeze in a three-and-a-half week residency in Mount Vernon with a little planning.

This approach has put our students in direct contact with professionals like David Apichell, the production stage manager at Madison Square Garden and touring stage manager for the Radio City Rockettes. It put actors onstage with David Combs, a member of the original Broadway cast of "Equus." Playwriting students are bouncing drafts off the likes of Naomi Wallace ("Lawn Dogs") and Keith Huff ("A Steady Rain"). And lighting designers are getting critical feedback from Stanley Crocker, touring designer for Sting and frequent designer for CMT's "Crossroads" and "Invitation Only" series.

And when we can't bring the artists here, the block plan allows us to go to them. It's not uncommon for my lighting design class to squeeze into a van and drive to Chicago to spend two hours with the production manager at the "Oprah Winfrey" show, or to tour the Electronic Theatre Controls plant in Madison with one of our two alumni employed there.

Could we do all of these things on a semester plan? Sure. You can make virtually anything happen if you work hard enough; isn't that what we want our students to believe? But if it's integral to the teaching approach rather than the exception, making it happen is the norm. It really is what you know that matters in the long run educationally, but who you know can really make a difference as well.

Scott Olinger (Photo by Aaron Hall '10)[/caption]

I recently found myself (as I often do) sitting in a darkened and hushed backstage corridor, speaking with a producer. The academic year was set to begin in a few days, and I had extended the opportunity to work on a special off-campus project to a few students who were returning early to staff events during new student orientation. The producer had commented on the quality of the student work and asked, "I suppose it's not every day your students get to meet an Olympic gold medal winner and work with a Grammy award-winning producer, eh?" I grinned and replied, "Perhaps more often than you would think."

One of the things my colleagues and I appreciate most about One Course At A Time is the unprecedented access it allows to guest artists. Don't get me wrong; we're not interested in shopping out our teaching responsibilities, but we jump at the opportunity to expose our students to an array of professional artists from all corners of our field. In a traditional semester plan, you can certainly bring in a guest to meet with your class for a few hours over the course of a week, or perhaps schedule a master class on a weekend. But imagine a four-hour master class for several days, a week, or better yet, an entire block. Most theatre professionals are used to living their lives on six-week rehearsal periods before packing up and moving to the next show, and it's often not too difficult to squeeze in a three-and-a-half week residency in Mount Vernon with a little planning.

This approach has put our students in direct contact with professionals like David Apichell, the production stage manager at Madison Square Garden and touring stage manager for the Radio City Rockettes. It put actors onstage with David Combs, a member of the original Broadway cast of "Equus." Playwriting students are bouncing drafts off the likes of Naomi Wallace ("Lawn Dogs") and Keith Huff ("A Steady Rain"). And lighting designers are getting critical feedback from Stanley Crocker, touring designer for Sting and frequent designer for CMT's "Crossroads" and "Invitation Only" series.

And when we can't bring the artists here, the block plan allows us to go to them. It's not uncommon for my lighting design class to squeeze into a van and drive to Chicago to spend two hours with the production manager at the "Oprah Winfrey" show, or to tour the Electronic Theatre Controls plant in Madison with one of our two alumni employed there.

Could we do all of these things on a semester plan? Sure. You can make virtually anything happen if you work hard enough; isn't that what we want our students to believe? But if it's integral to the teaching approach rather than the exception, making it happen is the norm. It really is what you know that matters in the long run educationally, but who you know can really make a difference as well.

One Course At A Time intensity fosters language learning

Devan Baty, associate professor of French

[caption id="attachment_17327" align="alignnone" width="573"]

Devan Baty (Photo by Aaron Hall '10)[/caption]

Learning a foreign language is a transformative experience. With each new word and expression, you see and experience the world in new ways. From the first day of French 101, you abandon your comfort zone. No longer a mere spectator or tourist, you become a direct participant in the global Francophone community by engaging with it on its own terms and in its own words.

The intensity of the block plan fosters a sense of community, which begins in the classroom. Students learn about each other and themselves while they are learning about French and Francophone culture. They not only study the form of the language, they also learn about the cultural contexts in which the language is spoken and lived. For example, a typical day's lesson in a language class under One Course At A Time includes a variety of activities, which build upon each other throughout the day. When learning about education, for example, students in Intermediate French begin by putting into practice new vocabulary and grammar to describe their own experiences at college. This is followed by a discussion of the differences between American and French educational systems and their impact on culture and national identity. Language students are most engaged when their learning is placed into a broader context. We bring that context to the classroom with culturally rich materials such as music, film, art, food, and literature.

The flexibility of One Course At A Time also allows me to take students off campus on short trips to neighboring towns to take advantage of opportunities to learn more about the world where French is spoken. I have taken students to visit an exhibition of Haitian art at the Figge Museum in Davenport, Iowa; to attend a lecture in Iowa City by Angélique Kidjo, a United Nations spokeswoman for child rights in Africa; and to sample pains au chocolat at a traditional French café in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Croissant Du Jour. I have also hosted students at my home for a traditional dîner gastronomique with multiple courses and conversation in French.

Since we can't leave the Hilltop every day to discover the wider Francophone world, I invite French speakers to join our community as frequently as possible. For example, students in an advanced-level course on French and Francophone culture had the opportunity to learn about the difficulties of cultural integration from a group of Congolese immigrants who visited our class from their new home in Cedar Rapids. Other class visitors have included native French speakers from Togo, France, Québec, and Luxembourg.

One Course At A Time has also inspired me to lead off-campus courses in locations such as Montréal, Canada; Fez, Morocco; and Aix-en-Provence, France. In a month's time, students make great strides in their speaking and listening skills by living with host families and engaging with local communities in French. Their cultural proficiency improves even more as they are forced to navigate the unspoken codes and customs of the society in which they are placed.

In the words of one of my French students: "Vive l'One Course At A Time!"

Devan Baty (Photo by Aaron Hall '10)[/caption]

Learning a foreign language is a transformative experience. With each new word and expression, you see and experience the world in new ways. From the first day of French 101, you abandon your comfort zone. No longer a mere spectator or tourist, you become a direct participant in the global Francophone community by engaging with it on its own terms and in its own words.

The intensity of the block plan fosters a sense of community, which begins in the classroom. Students learn about each other and themselves while they are learning about French and Francophone culture. They not only study the form of the language, they also learn about the cultural contexts in which the language is spoken and lived. For example, a typical day's lesson in a language class under One Course At A Time includes a variety of activities, which build upon each other throughout the day. When learning about education, for example, students in Intermediate French begin by putting into practice new vocabulary and grammar to describe their own experiences at college. This is followed by a discussion of the differences between American and French educational systems and their impact on culture and national identity. Language students are most engaged when their learning is placed into a broader context. We bring that context to the classroom with culturally rich materials such as music, film, art, food, and literature.

The flexibility of One Course At A Time also allows me to take students off campus on short trips to neighboring towns to take advantage of opportunities to learn more about the world where French is spoken. I have taken students to visit an exhibition of Haitian art at the Figge Museum in Davenport, Iowa; to attend a lecture in Iowa City by Angélique Kidjo, a United Nations spokeswoman for child rights in Africa; and to sample pains au chocolat at a traditional French café in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Croissant Du Jour. I have also hosted students at my home for a traditional dîner gastronomique with multiple courses and conversation in French.

Since we can't leave the Hilltop every day to discover the wider Francophone world, I invite French speakers to join our community as frequently as possible. For example, students in an advanced-level course on French and Francophone culture had the opportunity to learn about the difficulties of cultural integration from a group of Congolese immigrants who visited our class from their new home in Cedar Rapids. Other class visitors have included native French speakers from Togo, France, Québec, and Luxembourg.

One Course At A Time has also inspired me to lead off-campus courses in locations such as Montréal, Canada; Fez, Morocco; and Aix-en-Provence, France. In a month's time, students make great strides in their speaking and listening skills by living with host families and engaging with local communities in French. Their cultural proficiency improves even more as they are forced to navigate the unspoken codes and customs of the society in which they are placed.

In the words of one of my French students: "Vive l'One Course At A Time!"

One Course At A Time is ideal for field trips, research

Emily Walsh, associate professor of geology

[caption id="attachment_17328" align="alignnone" width="729"]

Emily Walsh (Photo by Aaron Hall '10)[/caption]

I love to tell my colleagues at other schools about the One Course At A Time system at Cornell. Often they are skeptical about teaching and learning on such a short calendar, but as I answer them, I get increasingly excited about all the positive aspects of the One Course At A Time system. For teaching geology, this might just be the ideal college schedule.

Why? The freedom of long class periods and the lack of other academic priorities for the students. The best place to learn about geology is in the field or in the lab where students can interact with the Earth, and with One Course At A Time I have the flexibility to take students out of the classroom. Even the most difficult concepts become clearer when you can stare at the rock, touch it, sketch it, follow it through the woods, hammer it, and examine it at length with a hand lens. As long as the field trips are in the syllabus at the start of class, I can schedule field trips of any length, ranging from half a day to several weeks.

Almost every geology course on the books at Cornell has a major field or lab component—even the introductory courses include several all-day field trips, and some are based around a series of field-based labs with little lecture involved. Majors are required to take at least one field course (the full block is spent in the field), and most of the upper-level courses include at least a weekend field trip. The first time I taught Igneous and Metamorphic Petrology, we (the professor included) were so exhausted by the end of three weeks that we decided to jump into a van and drive to southern Missouri to see the rocks in the field. No other system would enable such a spontaneous excursion. Since then, that three-day field trip has been part of the course syllabus.

Field trips benefit nearly every Cornell student who takes a geology course, but geology majors get the added benefit of research blocks. Every geology major at Cornell must complete at least one block of independent research; those who go on to graduate school after Cornell (a significant number) find out that a research block is the perfect way to prepare for the intensity and freedom of a graduate research schedule. Performing research during a block requires self-motivation as well as self-discipline; while the students have regular meetings with their faculty mentor and other students in the research group, the majority of their time is spent reading the literature, writing proposals and papers, performing research, and interpreting data. Any student who has completed such a research block understands the necessity for self-motivation and self-discipline in graduate school and has the tools to succeed.

At this point I may pause to take a breath, but I have already convinced my colleagues. They all wish they taught on the One Course At A Time system, too, and I realize again how fortunate I am to be teaching at Cornell College."

["post_parent"]=>

int(0)

["guid"]=>