The Cole Bin: Dating in the ’50s

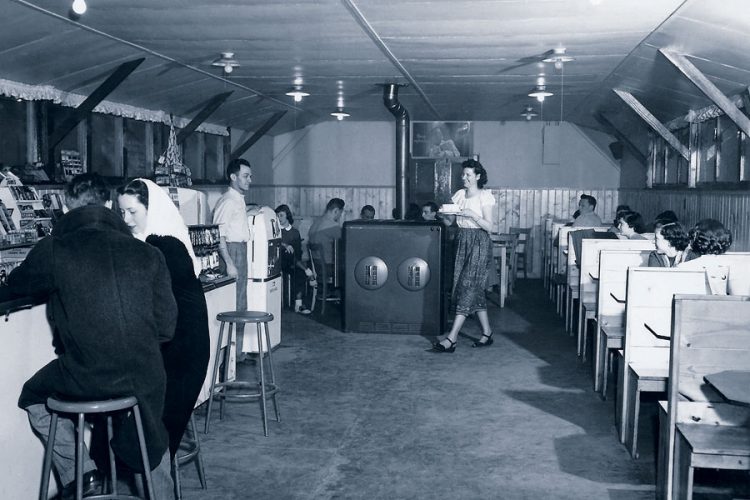

Dating on the Hilltop in the ’50s centered on the ramshackle, shedlike building known as the Cole Bin, with its aptly named Furnace Room (aka The Passion Pit). It masqueraded as Cornell’s “student union.”

At decade’s start the “in” spot was George Brown’s Quonset hut establishment, on an alley across the street from Brackett House. But when it closed in 1952, the only hangout for a game of bridge, dancing, and smoking was the white frame Cole Bin (successor to the original off-campus Cole Bin), located in the valley between Armstrong and Pfeiffer halls.

It was purchased as a World War II nurses’ barracks, and its name was a play on the name of then-President Russell D. Cole, Cornell Class of 1922, and the term coal bin (yes, in the ’50s there still were houses with furnaces fueled by coal stored in bins).

The room at the far end of the Cole Bin, housing one of the very few TV sets on campus, was named the Furnace Room. Darkened by drapes, equipped with sofas, and closed off from the rest of the building, you can imagine why it was rumored that when the TV was broken for more than a week, no one complained.

Students who staffed the short-order snack bar were charged with retrieving dishes and glasses as well as doing some cursory cleaning of the Furnace Room. To avoid curses from the couples occupying the room, various strategies were employed. One was to try to keep your eyes on the ceiling while cleaning up (no easy feat), but during my time as a counter person, I used the noisy approach—knocking chairs against the tables in the main room, loudly singing or whistling, and then pretending that I was having trouble turning the doorknob. That usually sufficed.

With only a handful of student cars on campus, it was not easy to find the privacy needed for serious dating encounters. Abbe Creek was wonderfully remote but had a short—nonetheless glorious—season. The also aptly-named Practice Houses (two former residences whose rooms were equipped with pianos)—checked on occasionally by a night watchman who was afraid of the dark—also gave shelter to young couples.

By today’s standards, perhaps the most shocking aspect of the Cole Bin was its unrestricted welcome of student smokers. One senior, a veteran of counter work, said he had considered bringing a canary to work to warn him when the carbon monoxide levels got too high. In the ’50s, with two out of three doctors supposedly endorsing a popular brand of cigarette, student hands also were busy holding cards (bridge was the “in” game), cups of coffee, and Chesterfields for hours at a time.

Business at the Cole Bin had its own rhythm, picking up when the daily (yes, daily) Chapel sessions were held, after a sports event, and on Friday evenings when the smell of fish cooking drove Cornellians away from the Pfeiffer and Bowman dining rooms. Students were allowed 15 Chapel cuts a semester, after which you had to pay the then significant sum of $1 a cut. Some daily Cole Bin regulars at Chapel time had connections with certain Chapel roll takers.

Other features of the Cole Bin, in addition to the food service area with booths against the walls, included a large, hall-like room complete with tables, chairs, jukebox, and Ping-Pong set. Dances were held there.

The offices of the Royal Purple yearbook were in the Cole Bin. And overall operation of the place usually was supervised by a local woman who kept the larder stocked and up-to-date.

Ah, but it was the way a relationship would progress—from playing bridge in the snack bar area, to dancing in the main hall, to an afternoon or evening in the Furnace Room—that comes to the minds of many alumni when the late, unlamented Cole Bin is mentioned.

The late Duane Carlson ’55 dated his wife-to-be, Ann Holcomb Carlson ’55, at the Cole Bin. He was vice president of communications for Blue Cross and Blue Shield for over 20 years. This story originally ran in 2000.

Read Gene DeRoin ’49’s essay on the first Cole Bin.

This story is part of a series on six student gathering spots, Hangouts through the years.