When cultures meet, sometimes they collide

As U.S. society experiences significant shifts in racial and ethnic demographics, a highly polarized electorate, a commitment to speech and academic freedom, and a lack of civility, it should not be surprising that our college campuses—like the nation as a whole—have been grappling with an escalation of racial tension.

Campuses like Cornell’s are tight-knit communities that, while valuing free expression, also place a high value on acceptance and inclusion of all community members. Unfortunately, that can’t always insulate college communities from the actions of a few.

A little over a year ago the Cornell campus experienced a series of racially charged incidents. As a result, the college engaged in a process of self-reflection to understand and address, systemically, how such disrespect for others could emerge on a campus where acceptance is an important value. The incidents prompted an agenda change in the Board of Trustees meetings a few weeks later to incorporate meetings with students, including students of color, to learn more about the campus climate. The college also engaged current faculty and staff in diversity education, and put additional emphasis on meeting the challenge of finding and hiring more diverse faculty.

Fortunately, these plus other initiatives, in the aggregate, made a significant improvement in campus climate at Cornell during the 2016-2017 academic year, as reported by Cornell students themselves.

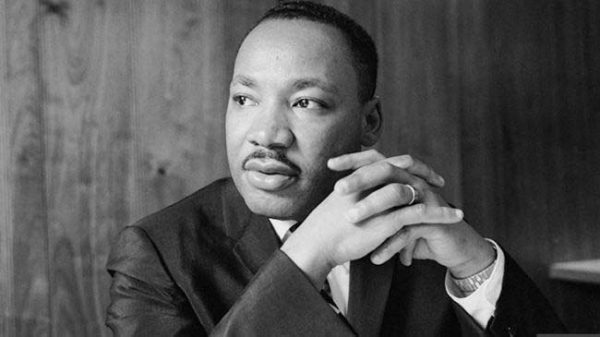

To better understand the issue of conflict around diversity, we can look to the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., in his speech at King Chapel on Oct. 15, 1962:

“I am convinced that men hate each other because they fear each other,” he told Cornellians. “They fear each other because they don’t know each other, and they don’t know each other because they don’t communicate with each other, and they don’t communicate with each other because they are separated from each other.”

The college believes, as did Dr. King, that people are more inclined to treat others with fairness and respect if they get to know one another.

WEB EXTRA: See the full script of Martin Luther King Jr.’s speech at Cornell in 1962.

Cornell has been diligent in its efforts to bring together a more diverse group of students. Today’s student body is 67 percent white, 24 percent people of color (including 12 percent Hispanic/Latino), and 5 percent international, with the remainder identifying as mixed race or not specified.

On the Hilltop students from 45 states, 20 foreign nations, and vastly different backgrounds live, study, work, and unwind in the intimate environment of a residential campus. It is an important step to bridging the separateness Dr. King spoke about.

The residential setting creates an amazing opportunity for students—as well as faculty and staff—to learn about the challenges others face and how to empathize with them. Coming together can enrich everyone’s experience, not just students in the process of learning who they are. Yet people don’t automatically know how to engage with others who aren’t like them.

Cornell in historical context

Since the college was founded, the evolution of social attitudes on the Hilltop has tracked with the American experience. In its first half-century, Cornell College was very much a reflection of American religious values, specifically those of the Methodist Church. Males and females were strictly segregated on campus, with a preceptress responsible for keeping an eye on the women. Events that included members of both sexes were closely chaperoned.

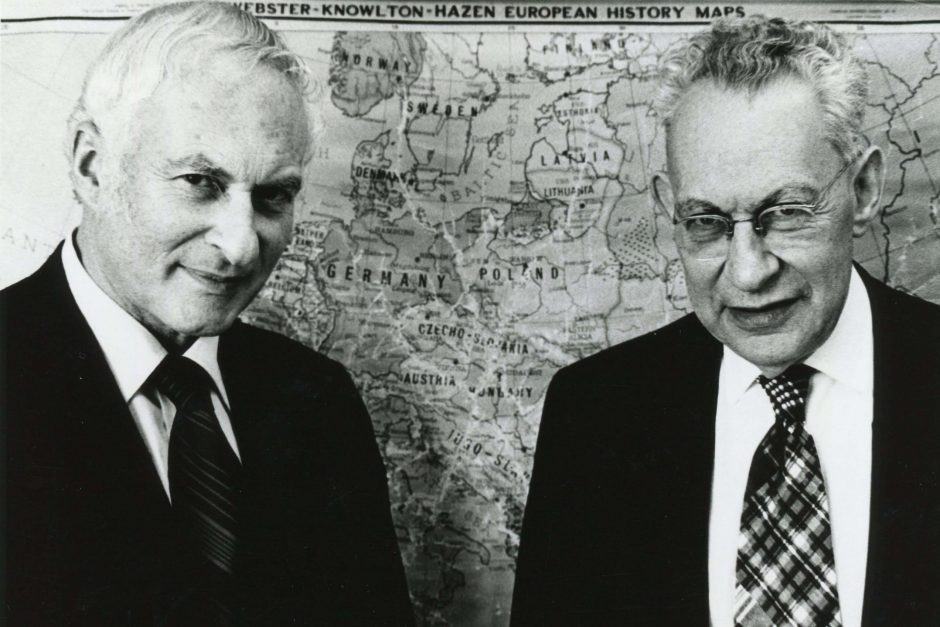

The first African-American man to graduate earned his degree 47 years after the school was founded. While women and men have been admitted on an equal basis from the beginning (the first graduating class was one man and one woman), females didn’t gain full acceptance on the faculty until a few decades later. Gradually, society became more inclusive, and Cornell followed the trend. The first tenured Jewish faculty member, Eric Kollman, arrived in 1945 (see related story).

As the civil rights movement took shape and grew in the 1950s and 1960s, Cornell again tracked with the country. Dr. King’s speech in 1962 was part of America’s awakening to the racial injustices in society. After racial violence in Selma and Montgomery, Alabama, in 1965 Cornell students organized a series of protests, including a 24-hour fast and vigil, a letter-writing campaign, and a march from campus to downtown. Later, 14 Cornellians went to Montgomery to help register African-American Alabamians to vote.

By 1968 there were more than 30 African-American students on campus, up four-fold from a decade earlier. Like their classmates, they were caught up in the horror of that year: Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in April, with riots in many major cities following. Bobby Kennedy was killed in June, followed by riots at the Democratic Convention in Chicago in August. After the well-known Old Sem student takeover on Oct. 17, 1968, courses about black history and black culture began to be integrated into the curriculum, and in 1969 a small black cultural center was established. Over the next several years, more African-American speakers were brought to campus to discuss racial issues. Efforts to recruit African-American students and faculty were increased, with limited results. As the nation’s turmoil receded, so did the unrest on campus. The issues faded, but didn’t go away.

Integrating marginalized groups

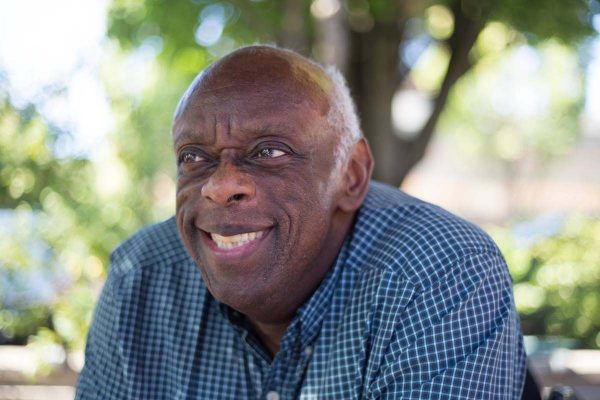

Rupert Kinnard ’79 remembers being marginalized. He came to Cornell as a gay African-American from Chicago at a time when Cornell was much less diverse.

Kinnard, who says he had a “great experience” at Cornell, remembers that a tree planted on campus to honor Martin Luther King Jr. kept getting vandalized.

“It was very depressing to know there were people on campus who would do that. It happened a number of times, and we kept replanting it. We went to President Secor to express our concern.

“He said we should plant it in the forest or honor Dr. King with a rock or something else that couldn’t be destroyed. He wasn’t getting it at all. We felt that each vandalism to that tree was an attack on us,” says Kinnard, who created the Brown Bomber, a gay African-American superhero comic that appeared in The Cornellian.

Then as now, the college grappled with the question of inclusiveness. It is one thing to recruit a diverse student body. It is another thing entirely to integrate everyone into the same fabric.

The issue is made more complicated by the fact that, as with most people, students tend to gather in tribes with people like themselves. Hemie Collier, Cornell’s interim director of intercultural life, calls it “staying in lanes.”

Responding to incidents

The nation’s political climate was getting turbulent during the spring 2016 presidential election season, particularly on college campuses. During Block 8, the Cornell campus found that our Hilltop home wasn’t immune. A group of racially discriminatory incidents created a sense of fear and distrust among many members of our college community, and elicited a strong and protective response from many of our faculty and staff.

Faculty and staff members decided to contribute to safety patrols, and to increase their accessibility to students who might need comfort or reassurance, by taking turns walking around campus during evening hours. Edwin R. and Mary E. Mason Professor of Languages John Gruber-Miller, chair of the Diversity Committee, noted that students also stepped up. “There were a lot of courageous, and angry, students speaking out against these divisive and targeted words at several speak-outs at the kiosks,” he said.

On April 17, President Jonathan Brand met with approximately 30 student leaders, Dean of Students Gwen Schimek, and several faculty members at Garner President’s House. The following day, President Brand held an all-college meeting in the gymnasium during which he told the packed house,

“… if your primary goal is to threaten somebody, to intimidate somebody, you think it’s funny to scare others, then I’m asking you now to figure out how to curb that behavior or leave the college right now and not return until you have that destructive behavior in check.”

President Brand, Chaplain Catherine Quehl-Engel ’89, Vice President for Student Affairs John Harp, and key administrators and faculty members met several more times with small and large clusters of student leaders to continue the conversations about campus climate. As a result, the college developed a 19-point action plan to address policies, communication, safety, faculty and staff development, diversity education, and community-building programming related to diversity and inclusion. Progress has been made, and the work is ongoing.

WEB EXTRA: View the video of President Brand addressing the full campus community during Block 8, 2016.

Per the action plan the college community worked together to write and approve a statement on diversity and inclusion. This statement is prominently placed on the website next to the college’s mission statement. Students, faculty, staff, and the Board of Trustees also recently confirmed a statement on freedom of expression and civil discourse, This statement affirms the centrality of speech, but also creates a clear expectation that Cornellians will choose to respect each other and their views.

In August 2016 an annual diversity and inclusion workshop for all employees was launched that will occur again this August, with periodic follow-

up sessions promoted by the college’s Diversity Committee.

In an ongoing effort to bring greater diversity to our faculty, the college adjusted faculty recruitment processes and utilized an Associated Colleges of the Midwest Faculty Fellows grant to place an emphasis on attracting candidates from diverse backgrounds. Among the four new full-time faculty members joining Cornell in fall 2017, three are people of color. In addition, the new Robert P. Dana Emerging Writer Fellow is a person of color.

New initiatives were implemented by student affairs to work toward building community among campus groups. Two all-campus assemblies and two convocations were held in 2016-17 to bring the campus together to explore and celebrate community. A Breaking Bread Series featured multiple activities for students, faculty, and staff to gather together around food, ideally with people different from those they interact with daily.

Furthermore, the Diversity Committee is sponsoring two academic initiatives for faculty consideration. One would revise the criteria for faculty reappointment, tenure, and promotion to encompass developing course material with a diverse audience in mind and creating a more inclusive learning environment. Another initiative would explore ways to enhance diversity and inclusion throughout the curriculum.

A Sustained Dialogue program was re-established as a system to transform identity-based conflict into productive conversation and learning. Several groups of faculty, staff, and students were formed and met throughout the year. Two student organizations, the Black Awareness Cultural Organization (BACO) and Third Wave Resource Group (TWRG) utilized Sustained Dialogue to partner in programs with talk-backs and dialogues.

“Sustained dialogue was a really great experience because I got to know my fellow students and some faculty better. We were able to talk through struggles we had been through, had seen others go through, and struggles that occur across campus as a whole,” says Carly Pierson ’17. “Through Sustained Dialogue, I learned about the issues people are interested in and how we can become more involved in addressing them.”

Cornell continues to adapt

Real progress in the current national political climate can be difficult. One certainty is that Cornell will keep the avenues of dialogue open. There are reasons for optimism, among them the presence of a faculty that recognizes the need to promote conversations about diversity and inclusion, a student body that seems far less divided than some, and a commitment to zero tolerance for expressions of hate against students.

“I think Cornell’s community is trying to move in the right direction to becoming a more inclusive and diverse campus,” says Nicole Casal ’18, who self-identifies as Asian-American.

“I would like to think that I have seen a wide spectrum of how diversity is shown on this campus, and I am glad to see a student body that is willing to make an effort and not only advocate for themselves but advocate for their peers in the ways that are needed.”

There’s also another, practical reason for students to learn to interact with others across the spectrum of differences: it enhances the probability of success.

WEB EXTRA: On Facebook: Cornell College Alumni of Color Network and Cornell College Pride Network (LGBTQIA).

“Diversity contributes more than anything else to what we call ‘emotional intelligence,’ which is the biggest predictor of leadership ability,” says Jodi Schafer, senior director of the Berry Career Institute. “People who have experience with diversity are better able to draw out the best in people. They work well in teams, consider different viewpoints, embrace diversity of thought, and can deal with complex problems.”

On a campus that is dedicated to student success, that’s a major reason to keep striving to address what might be the most important issue of our time.

MORE DETAILS:

- Cornell’s response to 2016 incidents

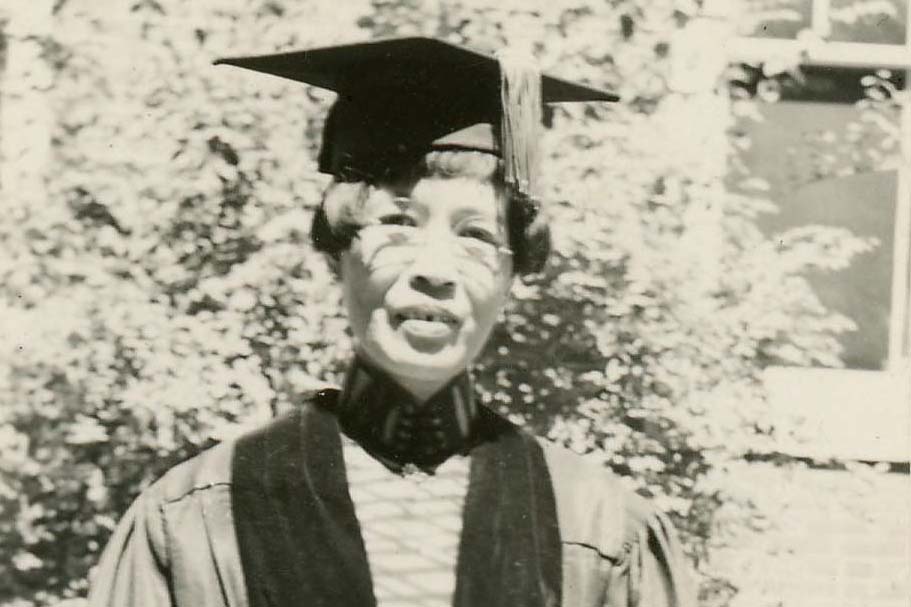

- Tale of two Asian alumnae

- First Jewish faculty were refugees

- History of Diversity at Cornell College