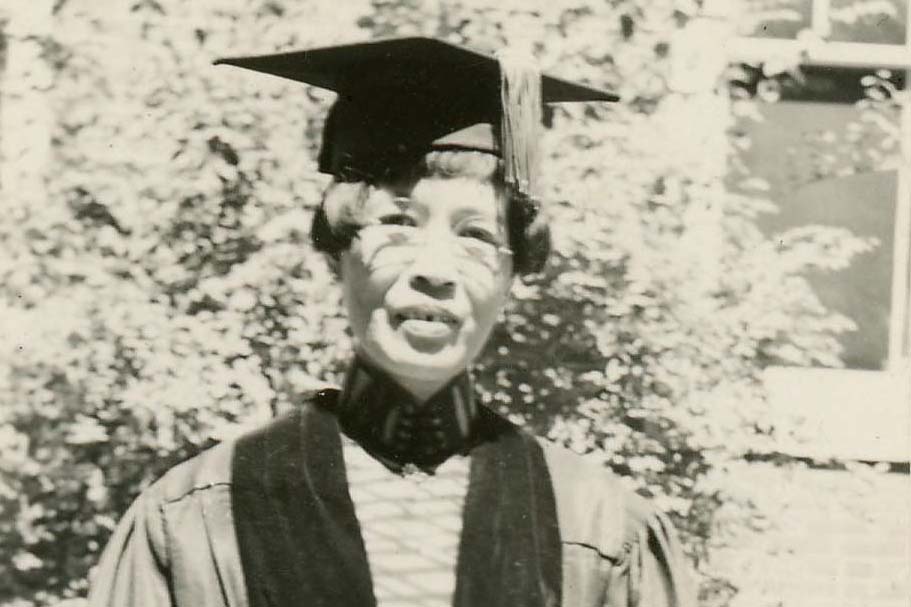

Cornell’s first female Asian-American graduate

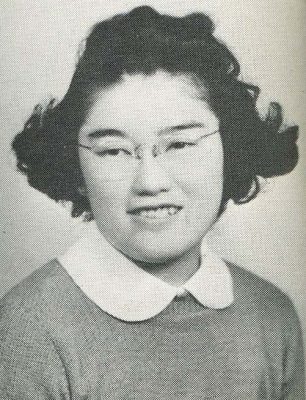

The first female Asian-American to graduate from Cornell was Masako Amemiya, who came to Mount Vernon in 1943 from an internment camp in California. She was one of about 5,500 young nisei (sons and daughters of Japanese immigrants to the United States) who were allowed to leave the camps to attend colleges in the Midwest and East. Amemiya had completed two years at the University of California-Berkeley before being interred in the camp. She completed her bachelor’s degree at Cornell in 1944. She returned to California after the war, married John A. MacFarlane, and died in 2010 in Los Gatos.

The following is an excerpt from the book “Storied Lives: Japanese American Students and World War II,” written by Gary Y. Okihiro and published by the University of Washington Press in 1999. Okihiro is professor of international and public affairs at Columbia University in New York City. Used by permission of the author.

Masako Amemiya MacFarlane recalled her first reaction to hearing of her acceptance. “Cornell College? No, not the university in New York State … It’s in Iowa? Yes. Oh. I had no idea where it was or anything about it, but when told that Cornell College was willing to accept me, I jumped at the opportunity without hesitation. It was an opportunity to leave behind the barbed wire fences, the armed guards, the cramped living quarters, and the line-up with plate and cup in hand for the mess hall.” She left her mother, father, sister, and brother for Mount Vernon, Iowa. “The moment I stepped off the train, I was warmly greeted by Dean McGregor and a student, Jan Appelt,” MacFarlane remembered. “I felt welcomed and began to feel that I belonged.” There were three other nisei students at Cornell College, Yoko Tada, Hank Fujii, and Tom Tashiro; and her two years there were “stimulating, eye-opening, heart-warming years.” Students invited her to their homes during the holidays and vacations, and her sister and brother were able to attend her graduation in 1944.

MacFarlane was born in San Francisco in 1920, and grew up in the city’s Fillmore District. Her father, Takeshige Amemiya, arrived in San Francisco shortly after the great 1906 earthquake, worked for a time in farm labor, went to Japan to marry Maki Muramatsu, and returned about 1913. Her older sister, Tane, was born in 1917, and younger brother, Minoru, in 1922. MacFarlane held fond memories of growing up in the Fillmore with other nisei children. The family’s social life revolved around the First Reform Church and its members. Her mother had grown up in a Christian family and attended Christian mission schools in Tokyo, MacFarlane graduated from Lowell High School, and for a year worked as a maid, the only kind of job that was open to her, she recalled. In the fall of 1939, she entered the University of California, Berkeley, where she was “on the outs” with the nisei crowd, although she joined the Japanese Women’s Student Club. Perhaps because of her loneliness, MacFarlane longed to go to a boarding school to get away from the Berkeley scene. But the war intervened, and she and her family were sent to the Tanforan Assembly Center.

There MacFarlane learned from the Student Relocation Council about the possibility of attending college east of the military exclusion zone. She applied, eager to leave the camp. MacFarlane was accepted by Elmhurst College in Illinois and gained her release from Tanforan, but just before she boarded the train, she learned that the local community in Illinois objected to having Japanese-Americans in their town, so her trip was canceled. With nowhere to go, she had to return to Tanforan to await another offer. The Relocation Council promised to find another college for her, and within two days, they told her about Cornell College.

The journey, recalled MacFarlane, was the “scariest train trip I’ve ever taken.” She was greatly excited about leaving until she got on the train. Once on board, she felt uncomfortable, because her fellow travelers eyed her suspiciously and, she surmised, must have wondered about this unaccompanied Japanese-American young woman who sat stiffly in her seat. Besides, she noted impishly, she had packed in her bag an alarm clock that ticked loudly. The people around her looked nervous, she thought, eyeing her luggage with its ticking contents. She didn’t say a word, and didn’t budge from her seat. A kindly African-American porter noticed her discomfort and brought her ice cream from the dining car. That helped to relieve some of her tension.

But once in Mount Vernon, Iowa, MacFarlane’s “most wonderful reception” made her feel instantly at home. Memorable during her two years at Cornell College were a history professor who invited her to have lunch with him and his wife on their farm outside of town, and her sociology professor who shared with her and other students the joy of bird watching in the early morning hours. She remembered especially a Christmas spent with a classmate and her family in Des Moines. “They accepted me,” she said, and were “just wonderful.” She formed a lifetime friendship and correspondence with that student and her family as a consequence. All of the college’s students, with the exception of the four nisei, were from the Midwest, MacFarlane observed, and the students, who were mostly women, totaled only around 600, with 78 in her graduating class. Cornell College, she gratefully recalled, gave her the most wonderful, horizon-widening experience I ever had.”