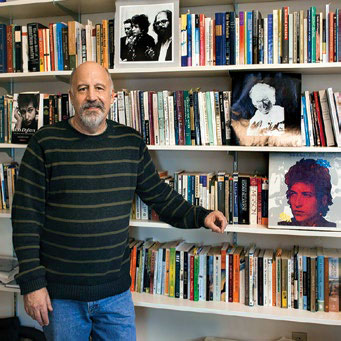

Tangled up in teaching Dylan

For 10 years now I’ve gathered with my first-year writing students and listened to Bob Dylan albums. From angry jeremiads like “Masters of War” to civil rights anthems like “Only a Pawn in Their Game” to the surreal circus parades of songs like “Desolation Row,” we listen and consider how poignantly Dylan’s words still speak to us today, in our era of Black Lives Matter and endless wars in the Middle East.

The subject took on added gravity this year when Dylan received the Nobel Prize in Literature. I could claim the award as vindication for my decision years ago to treat him as a scholarly pursuit, but it only adds a layer of complexity to teaching his work: is this “literature?” The Nobel committee posed a healthy challenge to literary scholars, the effects of which will filter through our discipline for years to come.

The subject took on added gravity this year when Dylan received the Nobel Prize in Literature. I could claim the award as vindication for my decision years ago to treat him as a scholarly pursuit, but it only adds a layer of complexity to teaching his work: is this “literature?” The Nobel committee posed a healthy challenge to literary scholars, the effects of which will filter through our discipline for years to come.

Critics point to his troubling misogynistic lyrics and behavior, or condemn his late ’70s religious conversion as just an opportunistic ploy, or argue that he sold out and be-came the very thing against which he once sang. The critics, in other words, beg us to consider if his work can stand up to such scrutiny as a class like this demands.

And Dylan? He doesn’t have much to say about any of it.

Ever since “Blowing in the Wind” became the refrain for the civil rights movement and Dylan became “the voice of a generation,” he has refused to take a stand. In rare interviews, he lies, avoids the big questions, and manipulates his audience, changing colors before his interviewers like a calculated chameleon. Again and again, he disavows him-self of his own words. Which is more important, I ask my students, the work or the life? Does an artist have a respon-sibility to take a stand?

They want to argue that it’s easy: Dylan should be free to write the songs he wants to write. But I push the question: is this the American Dream they imagine, to achieve success and then have no moral ob-ligation to act? Many of my students want to be writers or artists. Is it enough, I ask, to make a good piece of art and then not stand behind it? Don’t we all have a responsibility to act our conscience?

You’ll notice my prose is littered with question marks. I suppose, if I could claim one common trait with Dylan, it would be my inability—or unwillingness—to answer my own questions. I want, like Dylan, to prompt. As students attempt to unpeel Dylan’s work and life, layer by layer, the questions get more challenging and more relevant. The very contradiction and complexity of life in a democratic society is tangled up in the very riddles his life and work pose.

What I hope my students come to see is that Dylan’s ultimate message is that we must think for ourselves. That is how I want my students to respond. To think. To find their own conscience. And because it is a writing class, I urge them to speak. To add their voices to our ongoing American conversation. To write it clearly and to be heard.