A decade of Dimensions

Ten years ago preparation for medical careers at Cornell looked much like it did at many other liberal arts colleges around the country. Students got plenty of advising and a solid liberal arts education. It served generations well, as the many doctors who earned their undergraduate degrees at Cornell can attest. But Cornell isn’t like other liberal arts colleges.

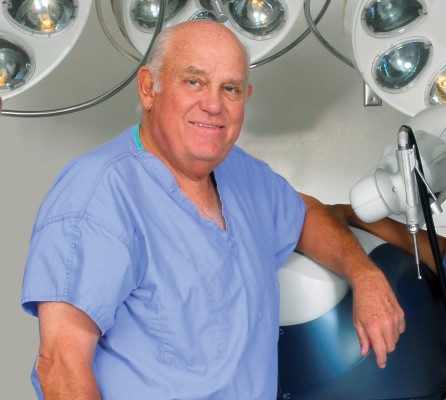

Enter Dr. Larry Dorr ’63. Dorr, an orthopedic surgeon and professor of medicine at the Keck Hospital at the University of Southern California, noticed that the medical students and residents he was meeting were so focused on the science behind their discipline that they didn’t know how to relate to their patients.

Medicine is a very personal field, Dorr said, and it’s not like sales where you have a product—the relationship is everything.

“You have to be able to deal with people,” Dorr said. “If you can’t, it doesn’t matter how much science you know. If you can’t initiate a conversation that instills confidence in the patient, you’ve struck out before you’ve started.”

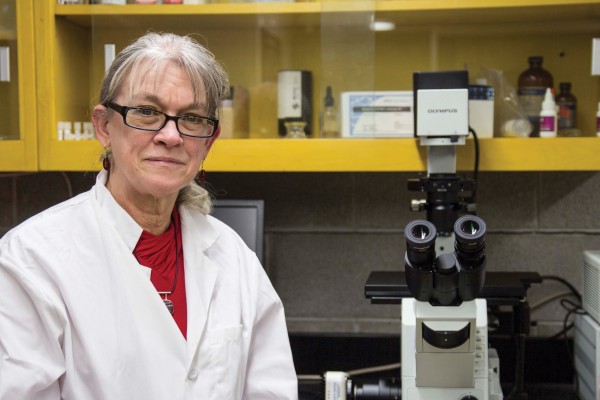

When he thought about it, he realized that a Cornell education might be the perfect antidote for the problems he’d seen. The liberal arts emphasis could help ensure that students who were going into health care had the skills they needed to understand the whole patient, not just their symptoms. He pitched the idea, and faculty were enthusiastic about it, in particular, biology Professor Barbara Christie-Pope.

“Without her it wouldn’t have happened,” Dorr said. “I had the idea, but the faculty and staff made it work. Barbara took the idea and developed it, and it wouldn’t have become what it is without her energy and enthusiasm.”

students to benefit from Dimensions, is

now a physician in Mount Vernon, Iowa.

She said her experience on Operation Walk

during her senior year at Cornell was the most patient contact she’d have until her residency.

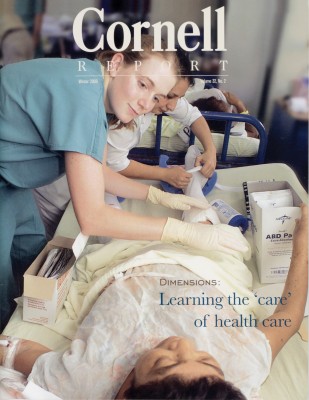

The students who heard about the idea were enthusiastic too. Dr. Jamie Wallace Smith ’05 served on an exploratory committee, along with Christie-Pope, other faculty members, Dorr, and another student, Kent Lehr ’06. Smith, who grew up in Mount Vernon, Iowa, and is now a physician in town, remembers the committee discussing how other disciplines could be brought into students’ preparation for medical careers. They thought about what other disciplines might be relevant and how a curriculum might be structured. They thought broadly about how to best prepare students not only for medical school, but for any career in health care, Smith said.

During one of those committee meetings, Smith was asked to go on the first of what would become the most prestigious experiential learning opportunities that Dimensions sponsors—Operation Walk. The organization, which Dorr founded, provides free orthopedic surgery for patients in developing countries. Smith and Lehr went to El Salvador with a team of doctors, nurses, and physical therapists and observed and helped to treat patients. In fact, Smith said, the contact she had during that trip in her senior year was the most contact she’d have with patients until she was a medical resident.

Programs like Operation Walk, which still regularly takes Cornell students abroad, are part of what makes Dimensions special, Christie-Pope said, but the real key to the program’s success has been the focus on students and their needs. The one-on-one health professions advising and the options available for internships, research, and graduate or professional schools has made the program last for a decade, she said, because it sends students out into the world ready for careers or for further education.

The support from alumni has also been key, she said. Some, like Mayo Clinic breast cancer researcher Dr. Jim Ingle ’66, have come to campus to lecture. Dimensions also connects students interested in a particular field with alumni working in that field. Those relationships help students decide on a path.

“I don’t know if Dimensions would have flourished the way it has without the tremendous support from our alumni,” she said.

Cornell’s 2008–2014 medical school acceptance rate is 79.2 percent, compared with a 41.2 percent national average.

Medical school and physical therapy are the top two programs of interest, but students have also gone into public health, research, and even hospital administration. That mix has kept the program growing and vibrant, and able to serve more students across campus.

The basic idea of Dimensions has resonated with medical and graduate schools, Christie-Pope said, because Cornellians arrive better equipped to deal with patients on a personal level. And the liberal arts foundation that Cornell offers helps Dimensions students when they’re applying for programs. The students aren’t just focused on science, she said, and they’re able to write well, which makes formulating a personal statement easier. They’re able to draw connections, and that’s something the program emphasizes.

“Dimensions tries to get students to realize that every course they’re taking gives them background that they can use later on,” she said.

And that effort seems to be working to turn out attractive candidates. Cornell’s 2008–2014 medical school acceptance rate is 79.2 percent, compared with a 41.2 percent national average.

The idea of creating more humane medical professionals is important to graduate and professional schools, she said, but it’s difficult given the amount of science that students in health-related fields must learn.

“For some of them, Cornell might be the last chance to get a liberal arts perspective on health care,” she said.

That depth really makes a difference, Smith said. She minored in anthropology and did a research project on medical practices in different countries and cultures. That research made her more aware of how her patients might be thinking and feeling when she’s treating them.

Over the past decade the program has continued to expand. Christie-Pope sees more opportunities to integrate Dimensions programing with disciplines related to health care, even if they aren’t directly a part of it. One example is science writing. Author Sam Kean—whose most recent book, “The Tale of the Dueling Neurosurgeons,” served as the text for a neuroscience class Christie-Pope taught last fall—visited campus in January. He’s an author, but his three books have each been about science, and his most recent one was directly about medicine and health care and how they have evolved. Visits like this show students across campus that there can be a lot of room under the health care umbrella.

The expansion of Dimensions, and of the fields for which it helps prepare students, has shown Smith the significance of the program she helped shape. At the time she didn’t necessarily realize that she was helping to form a longterm program that would offer students preparation for so many different fields. But, looking back, she’s glad she was part of it and pleased with what Dimensions has been able to offer.

“Hopefully it sends students into their respective programs with their eyes wide open,” she said.