A liberal arts education, John Steinbeck, and me

John Steinbeck, the writer whose life and works have shaped my academic career, was a middling student at Stanford University, where he enrolled in 1919. Exactly 50 years later, I threw off my Cornell College freshman beanie as exuberantly as he tore off his shirt for Stanford’s annual freshman/sophomore tug of war—a man’s unsheathed torso was a shocking public display at that time. Like Stanford in 1919, Cornell College in 1969 offered many distractions for a giddy freshman: broom hockey in January; picnics at the Pal; and parties at Pfeiffer Hall—with maybe a bit too much cherry vodka added to Sprite. Heady freedom ensnares.

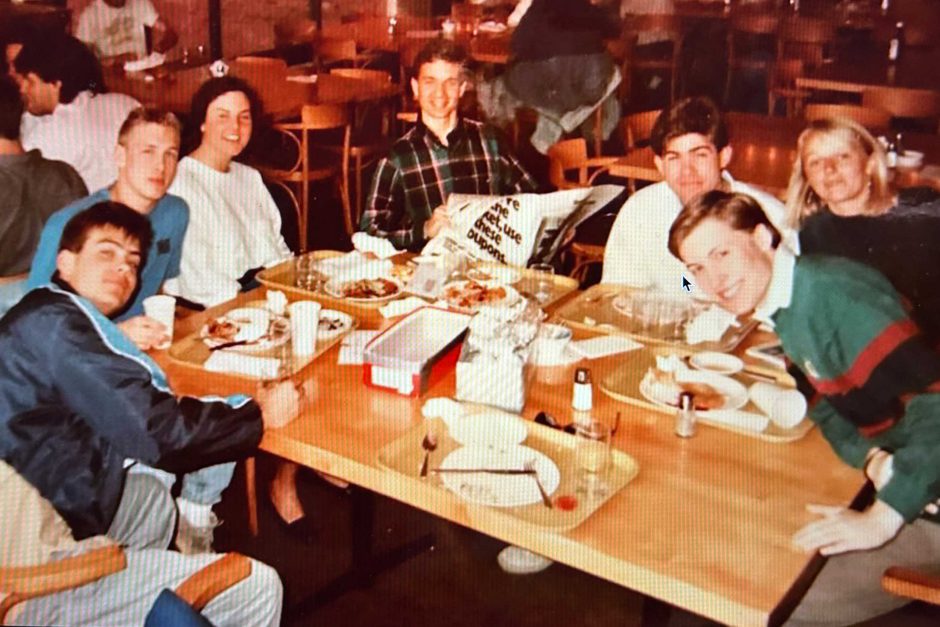

After a couple of half-throttle quarters, Steinbeck dropped out of Stanford, although he returned sporadically during the next five years to take creative writing courses and world history. My own undergraduate career, thankfully, took a different trajectory from his and I earned, as he did not, a B.A. in English and art. But I believe that Cornell grounded me in the same ways that Stanford grounded Steinbeck: Ideas matter. Startling friendships endure. A spirit of inquiry untethers a curious mind from easy assumptions. Stanford’s motto, “The wind of freedom blows,” eventually meant more to Steinbeck than a bare chest. “I think rebellion is man’s highest state,” he wrote to a college friend a year before he left the university. He would stake his career on that notion of freedom.

Now I am a professor of American literature at a state university in California, and I have a tough time explaining to my own students—many of whom work 20 to 30 hours a week and commute—the great gift of a liberal arts education at a small college in the Midwest, or anywhere else. Four years to transition from “flibbertigibbet”—Steinbeck’s description of his own collegiate lapses—to scholar, so that reading Light in August, as I did as a senior, is electrifying and hearing Rob Sutherland on Herodotus is life-altering. Four years to join a phalanx of other questers. Four years to cement friendships. (Friendship is the most resonant bond in Steinbeck’s fiction—“Tell me about the rabbits, George.”). Let’s remember the German chocolate bars, Ginger.

Stanford tugged at Steinbeck’s heart. Long after he left for good in 1925, he sent his stories to Edith Mirrielees, his creative writing teacher—one of “about three” of his great teachers.

“[S]he had only two rules—know what you want to say … say it.” And from “The Grapes of Wrath” to “The Winter of Our Discontent,” he drew on those incantatory lectures on world history. Although he wrote to a college friend in 1964 that he would be embarrassed to go back to campus because he was “such a lousy student,” in that same decade he decided to bequeath his Nobel Prize (1962) to the university that launched his writing career. Perhaps we are all just a bit insecure?

I do go back—most recently on a road trip last summer with my husband and dog—Charley, of course. We parked our red Toyota pickup on campus. Charley swam in Ink Pond. I explained the Rock to my puzzled husband. And we chatted with professors who mattered then—and now. Cornell is lodged in my heart. While I didn’t study John Steinbeck at Cornell—that would come much later—I have not forgotten my professors’ own passionate writerly love affairs: with John Milton (Elizabeth Isaacs) and Yukio Mishima (Robert Dana) and William Faulkner (Richard Martin) and Robert Browning (Geneva Meers). In the art department, Hugh Lifson challenged my every artistic assumption: one day he hurled red paint at a male model, his response to the war in Vietnam. Doug Hansen merrily taught me to see—and patiently to create beautiful pottery objects that mattered.

And now I find myself in northern California next to the great Pacific Ocean. There are few days here without the winds that have swept across that watery expanse, blowing east—each gust taking a part of me back to the place that first unbound my thoughts. For Steinbeck, for me, for all of us—let the winds bring us freedom.