Symposium stories

Students at Cornell write dozens of papers during their time on the Hilltop. They give presentations every month and analyze works of art weekly. They perform experiments and experiment with performances.

But one paper, one presentation stands out: Student Symposium. Working closely with faculty members who often grow into mentors, Cornell’s best and brightest are afforded the opportunity to fully delve in and develop a topic. They present their knowledge to the community yearly in order to further their scholarship and enlighten us all.

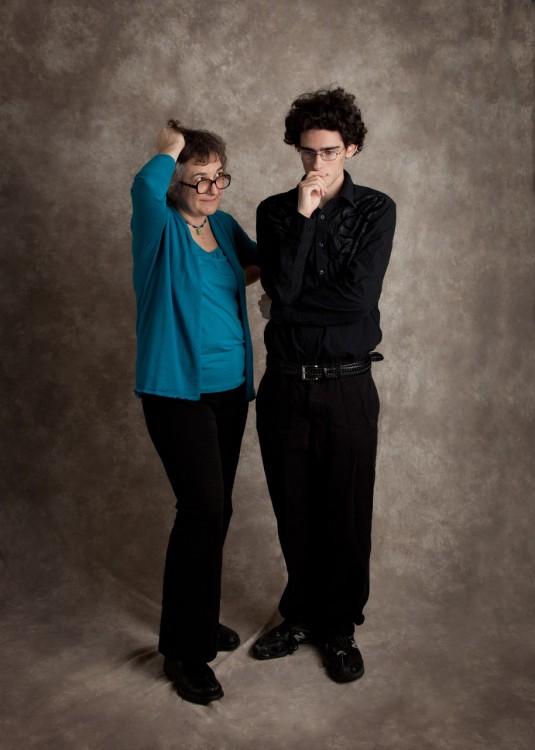

A “master’s level” theatre project

• Subverting Stereotype: Reconstructing Euripides’ Medea •

It would be difficult to walk away from a discussion of theater and his Student Symposium presentation with senior Alec Hynes and not feel at least a little bit intimidated.

“I’ve never met an undergraduate student with the sense of self and the sense of grounding necessary to do this project,” said Theatre Professor Janeve West, who served as Hynes’ advisor on his symposium project. “It was a master’s thesis level project.”

The project in question was a deep, original retelling of the ancient Greek tragedy “Medea” by Euripides. In the original, the title character seeks revenge on her husband Jason—of Golden Fleece and Argonauts fame—by killing their children and his new wife-to-be.

In Hynes’ version, the audience meets Jason decades later and hears the version of events from his perspective. Hynes drew the text from multiple sources and even wrote some of it himself.

The idea to produce his own version of the Greek tragedy grew out of both the small notion he had of Jason revisiting the story years later and Hynes’ own desire to begin feeling his way around the world of professional theater.

“I was having some concerns about what doing professional theater would be like—what it would be like not having enough money—and I was also worried about not having enough artistic control,” Hynes said.

So he took control.

Hynes was in charge of every aspect of the production from start to finish, from concept to conclusion. He deconstructed the play and put it back together, weaving ideas on gender—females played some male roles, males played some female roles—audience engagement, and contextualization into an otherwise familiar story.

“He had a very clear vision, a very clear vision,” West said.

West came to work with Hynes on the project somewhat gradually. She was new to Cornell last fall but had met Hynes when he served as a student on her search committee. The professor left an immediate impression on Hynes.

“I’m enthralled with her process,” Hynes said. “It was very organized and I’m not a very organized person.”

He also needed a sounding board. While the project was clearly an important one for Hynes to do on his own, he readily sought advice from West. She, in turn, was always ready with a question to help Hynes find the right direction.

They developed a relationship that was as much professional as it was teacher-student. Hynes continued to work with West well after his project was done, starring in her production of “Cloud 9” in dual roles.

Hynes, who comes from Glenwood Springs, Colo., plans to expand his repertoire. He starts at Case Western Reserve University this fall where he will pursue an M.F.A. in acting—a program that only accepts eight students every two years. He received a full tuition scholarship.

“Alec has an absolutely bright future,” West said. “He has a clear vision of what he wants to do, and he also knows what kind of an artist he wants to be. And that generally comes after a significant amount of life experience.”

Wagner, animals, and academic curiosity

• Wagner: Purity, Animals, and Vegetarianism •

For many Student Symposium participants, the day is something of a capstone to their work at Cornell—a final presentation that demonstrates how far they’ve come in their scholarship over four years of work in their chosen field.

For others, like sophomore Audrey Zannini, it’s a chance to experiment and explore academia and all of the weird and interesting topics that might pique their interest. In Zannini’s case, she combined an academic curiosity about Richard Wagner with a love of hers that most people don’t often associate with the 19th century German composer: “I love animals. I’m very into their welfare and care,” she said.

The result of that combination was a presentation titled “Wagner: Purity, Animals, and Vegetarianism,” a look at how Wagner, specifically his opera “Parsifal,” demonstrated a view of animals that deemed them pure and innocent and conveyed the goodness of the world—much like how Zannini herself views animals.

Zannini’s love of animals doesn’t stop with Wagner scholarship either. She has pets of her own and volunteers at animal shelters in both Iowa and her native Arizona, teaching to-be-adopted pets basic commands, cleaning up after them, walking them, and socializing them.

It was Music Professor James Martin who put Zannini onto Wagner and later encouraged her to refine the paper and turn it into a symposium presentation. Martin taught a class at Chicago’s Newberry Library called Wagner and Wagnerism, for which Zannini originally wrote the paper.

Martin, a big proponent of the symposium, saw the potential in Zannini’s work.

“The topic was interesting. For one, with Wagner, any time you become involved with the topic of purity, it can be interpreted, at the kindest, as nationalism, and, at its worst, racism,” Martin said. “That makes the topic fraught with importance.”

It also, he thought, gave Zannini—who he has known since her first block of freshman year—an opportunity to focus academically while still trying new things.

“She has genuine interests in so many things. In a sense, being at a liberal arts college like Cornell is perfect, because she can explore all those things,” Martin said. “But there will come a time when she’ll have to decide to focus on one thing or another.”

And Martin certainly helped her do that. Together they honed Zannini’s speech and found ways to showcase Zannini’s points to a wider audience.

“He definitely helped me focus my thoughts to make sure I got across what I wanted to my audience,” she said.

Martin said much of the value of the symposium is in experimenting with the process, which is why he thought it was a perfect opportunity for Zannini’s budding academic curiosity.

“This is the perfect time in her life to be exploring these things. She’s getting the most out of being here,” Martin said. “Is there a danger of spreading oneself too thin? Sure there is. But she’s discovering. How can you not like that?”

A lovely storyteller emerges

• Kurosawa’s Ran and the Jidaigeki Genre •

When Connor Haines took a 200-level film studies class with English Professor Katy Stavreva last year, he could have easily slipped through the class without much fanfare.

The freshman from Ann Arbor, Mich., was quiet in class, Stavreva said, and understandably so, since he was likely the youngest one in it. But his work was so strong, his writing so intriguing, that Stavreva eventually tapped the now-sophomore to present his paper on Japanese cinema at Student Symposium this year.

Haines was one of two students in the class who impressed Stavreva, but it was more than the paper that caught her attention. It was Haines’ voice in a series of film studies journals that really piqued her interest.

“It was very precise and thoughtful. I got a sense of a dialogue between him and the film,” Stavreva said. “They read like screenplays and had this real sense of voice, a real sense of an interrogation of the films. He was like the hardboiled detective. It was not a voice I had heard in class before.”

Stavreva says Haines’ interest in Japanese cinema led to an engaging and insightful look at the genre.

“He’s a really lovely storyteller,” Stavreva said.

And he certainly is: Ask him about his symposium project—an analysis of Akira Kurosawa’s “Ran” and the Japanese “Jidaigeki” genre—and you’ll feel as if you saw the film yourself.

He deftly describes the film—a Jidaigeki, or period piece, about the breakdown of a once-powerful Japanese family—while simultaneously breaking down how “Ran” differs and deviates from the genre in very important, very telling ways.

“Essentially what Kurosawa did with ‘Ran’ is he reversed the traits of the protagonist and the antagonist. The protagonist has oppressed and controlled, but he’s sympathetic, while the villain is someone who has had her family killed and is acting out of revenge,” he explained. “Just based on those traits, they’d be swapped, but the way that they’re portrayed, she’s an unambiguously evil character.”

It was because of Haines’ strong work on his analysis of “Ran” that Stavreva suggested he present it as a symposium project. The work was already polished enough that the pair met just once to refine the paper before Haines presented at symposium.

“That was very nerve-wracking,” he said of symposium. “But it was a really good experience. I got a lot out of it. The presentation itself went quite well.”

Stavreva agreed.

“He was extremely professional and really precise,” she said. “I get students like that, but they’re usually seniors.”

The symposium presentation pulled Haines out of his shell in Stavreva’s eyes. He had been a strong, but quiet, student throughout class, but she saw him transform a bit over the course of getting to know him.

“I had no idea that Connor had a sense of humor, but I discovered that he was very funny,” she said. “If it hadn’t been for his written work—which was consistently good and consistently surprising—he would have slipped right under the radar.”

Water quality project provides capstone

• IOWATER and Phosphate: A Study on the Effectiveness of Volunteer Water Quality Monitoring Programs •

Chemistry and politics might seem like strange bedfellows, but in senior David Elston’s Student Symposium project, there was plenty of common ground to be found.

Elston’s project, “IOWATER and Phosphate: A Study on the Effectiveness of Volunteer Water Quality Monitoring Programs,” played in the intersection of public policy and science by looking at the quality of Iowa’s volunteer water monitoring program in order to press the basic question of whether good science was driving the state’s water policy.

For Elston, water has always held a certain fascination. He developed an interest in both the treatment of and policy around water early on, thanks to his father’s job as a water plant operator. He brought that interest with him to Cornell, where he majored in politics and environmental studies with a minor in chemistry.

And when a class with Chemistry and Biology Professor Brian Nowak-Thompson took Elston to the boundary waters to do some quality testing, Elston knew he had found the topic that would become both his symposium project and the capstone to his environmental studies major.

He also knew he wanted to explore his interest in water policy, specifically the intersection of water quality monitoring programs—in this case, Iowa’s IOWATER volunteer testing program—and how those programs’ effectiveness could affect state policy.

“I always wanted to look into the policy around water testing. I thought it was interesting,” Elston said. “I really did think what I had was a good idea.”

So did Nowak-Thompson.

“I think what impressed me most with David’s approach was that it wasn’t just going out and taking water measurements, it was really looking at the data gathering process,” he said. “It was a very sophisticated approach for a student.”

Elston said he felt he was already strong in the area of policy, but knew he would need some help with the actual water testing. He said he had enjoyed working with Nowak-Thompson before, making the decision to turn to him for help on the actual chemistry a fairly easy one.

That, in turn, led to an interesting working relationship between Nowak-Thompson and Elston. Policy isn’t the chemistry professor’s area of expertise, so much of the conversation centered around the what and the how of water testing.

Most of our conversations were about how to monitor the water quality. David occasionally had questions about the technical side of things,” Nowak-Thompson said. “He often just checked in with me and said here’s what I’m going to do this month.”

The result was a project that both Novak-Thompson and Elston said offered a bit of a twist on most projects that looked at water quality.

“I was tackling this differently than other people might,” Elston said.

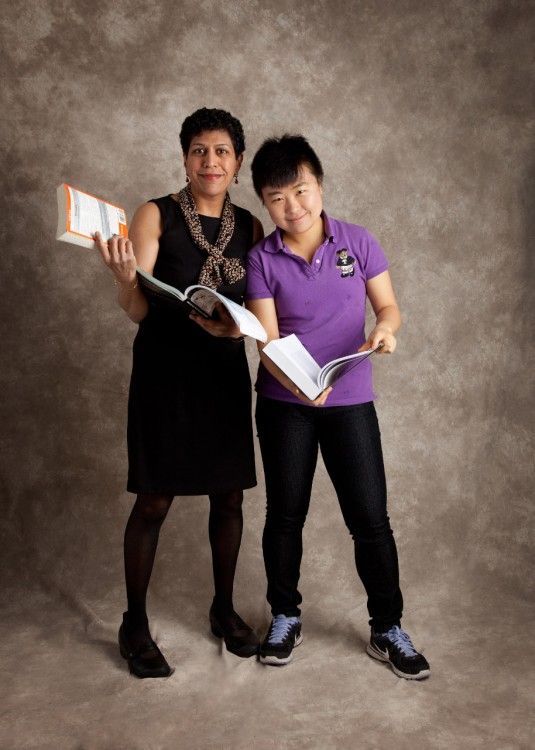

Project grooms student for grad school

• How Do Your Friends Make You Fat? An Economic Approach to the Network Effect and the Spread of Fast Food •

When senior Herbie Huang presented “How Do Your Friends Make You Fat? An Economic Approach to the Network Effect and the Spread of Fast Food” at this year’s Student Symposium, it was about much more than the topic she had spent months researching and refining.

Granted, her topic was pretty cool. She developed an economic model that maps the spread of obesity across social networks, providing a possible mechanism for how obesity spreads through the population.

But for Huang, it was the work she did with Economics and Business Professor Santhi Hejeebu that may end up mattering most as Huang moves on to graduate school in economics.

Huang came to Cornell by way of China, meaning that while she’s a talented mathematician and economics student, learning to write in English was a hurdle she knew she’d have to overcome to continue her march up the academic ladder.

She had worked at the Writing Studio and utilized Cornell’s other resources, but it wasn’t until Hejeebu—who had never taught Huang or even met her—took her under her wing for a summer that she began to feel truly prepared for advanced academic study.

Hejeebu had heard from a colleague that Huang had completed a program for complex systems that involved considerable work in economics that Hejeebu knew to be very difficult. Her interest and curiosity piqued, she approached Huang to discuss the program and her future in economics. Seeing something special in Huang, she invited Huang to work with her over the summer.

“This is a pretty motivated person. She’s a real self-starter. She had proved that point before we even met, and that’s a key quality for any scholar,” Hejeebu said.

The pair spent the summer doing research and working through a textbook on social networks. When they weren’t hard at work on that summer project, Hejeebu worked with Huang to improve and refine her English writing in preparation for graduate school, while also challenging her to learn more about economics.

“She really helped with writing. I feel like I’m much better prepared now,” Huang said. “She is just pretty much my mentor in terms of leading me toward economics and showing me how to be a good economist.”

That opportunity to work one-on-one, Hejeebu said, is what differentiates the Cornell experience from other larger colleges. Self-motivated students, with personal help from faculty members, can absorb several topics at the same time. Huang immersed herself in humanities, language, and communications while working toward a B.A. degree in mathematics. She is well-prepared to pursue a Ph.D. in economics.

Hejeebu said her summer work and subsequent symposium work with Huang was one of the best experiences she’s had with a student.

“Anything that I expected to be done was already done. I didn’t need to ask her twice. If I could extract that from her bloodstream and inject that into my other students, I would do that in a heartbeat,” Hejeebu said.

That hard work paid off. Huang has enrolled in the graduate school in economics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Hejeebu said she has no doubt Huang will accomplish anything she sets her mind to.

“Nerdy” team works well together

• North Korea’s Nuclear Program: The Failure of Sanctions •

Sometimes a mentor-mentee relationship just clicks. Both people think alike, talk alike, and live in the same worlds, and that helps define how they work together. In the case of junior Jennifer Knox and her symposium advisor, Politics Professor David Yamanishi, they have one pretty big personality trait in common.

“We’re pretty nerdy,” Yamanishi said.

Yamanishi, who also serves as Knox’s academic advisor, found he had a lot in common with his advisee. Both enjoyed fantasy games and novels, word puzzles, and, of course, have an interest in public policy.

Knox’s principle policy interest is in worldwide nuclear disarmament, a topic she has passionately pursued for as long as she’s been at Cornell.

“Jennifer has been working on a version of this argument for three years now, all the way back to her first class with me,” Yamanishi said of a first-year class that helped spark Knox’s pursuit of a degree in international relations.

It was another Yamanishi class that spurred Knox’s Student Symposium presentation, “North Korea’s Nuclear Program: The Failure of Sanctions.” In her presentation, the former volunteer for President Barack Obama’s re-election campaign argues that, as the title suggests, the administration’s approach to nuclear program-related sanctions hasn’t passed muster.

“The conclusion I came to is that political and economic sanctions need to be used in conjunction,” she said. “The failure relates to moderation. Either commit to a fully cooperative or a fully confrontational strategy.”

The paper’s point was to illustrate a flaw in current United States international policy, but Knox’s bigger goal is to work toward the dismantling of nuclear weapons around the world. It’s a passion that has also led her to partner with another mentor of sorts—Derek Johnson ’04 of Global Zero, a group dedicated to eliminating nuclear warheads completely. Knox, of Richardson, Texas, is president of the Cornell College chapter of Global Zero.

Yamanishi had no problem challenging Knox’s deeply held views both in class and while shaping and honing her symposium presentation.

“He’s a devil’s advocate, for sure. Any time you try to make a point, he argues the other side to help refine your argument,” Knox said.

Yamanishi neatly echoed Knox’s take on their student-teacher back-and-forth.

“It’s relatively easy to play devil’s advocate, because the bulk of international scholars are on the opposite side of the deterrence issue from Jennifer,” Yamanishi said. “I think it forces her to refine her arguments and address points that might seem sort of natural to her, but would be contrary to the literature.”

Neither the literature she’s combed for her research, nor Yamanishi’s incisive questions, have stalled Knox’s pursuits. When she graduates from Cornell next year, she plans to continue pursuing her studies in nuclear policy, possibly in graduate school.

And Yamanishi, for his part, has no doubts she’ll go far.

“Her strength is that she’s just really passionate about this issue, but still self-critical enough to know how to present her arguments,” Yamanishi said.

“She’s also, of course, extremely smart.”