Why athletics matter to Cornell

Every year when the Iowa air has turned crisp and cold, the campus seems to hold its breath in anticipation of a ritual that has been repeated for decades. Waves of students, faculty, staff, and community members pack themselves into the gymnasium.

Friends and hall-mates pile in wearing matching homemade T-shirts under bulky jackets, often carrying banners made in the Thomas Commons notched under an arm, waiting to be unfurled at the right moment.

When the gym is full to bursting, just when the crowd begins to get restless, the friends and classmates they came to see run onto the floor. Every step they take and every move to the basket is a bit quicker. They feel it too.

And then it happens.

Whoosh.

If the night is clear, the roar that erupts from the Small Multi-Sport Center can carry up the hill, and students who didn’t or couldn’t brave the crowds look up or cock an ear to the sound of mayhem coming from the gym. Because they know.

They know that, as the din subsides, the gym floor is completely, utterly, and spectacularly covered in toilet paper.

For a campus that wraps itself in history like a warm winter cloak, the toilet paper toss that accompanies the first basket scored by Cornell College in its home game against rival Coe College is a relatively young tradition, even if it is revered among students.

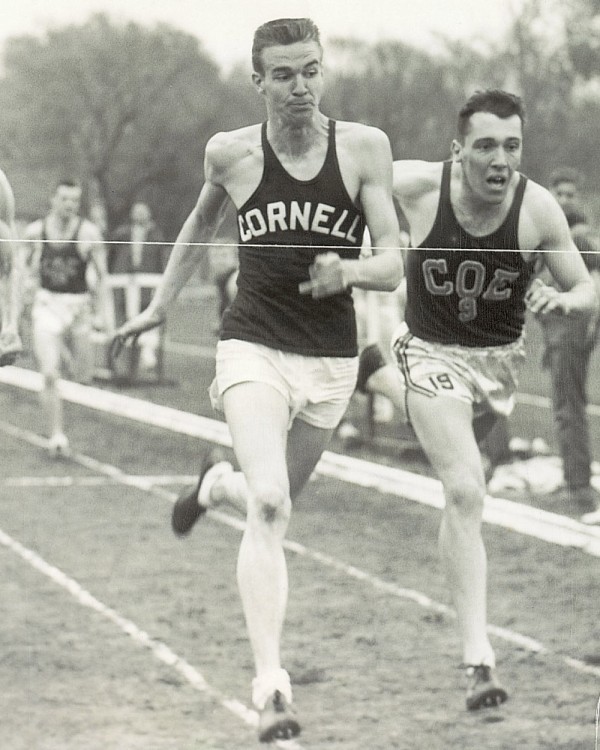

But the rivalry it celebrates, the Coe-Cornell contest that has stretched back to 1891, is emblematic of the long and storied tale of athletics at Cornell that echoes from the longest rivalry west of the Mississippi to a modern day program embracing a new spirit and renewed focus on the student experience.

“We realized early on—before March Madness and the Bowl Championship Series and the Rose Bowl—we were doing athletics because we thought it was part of educating complete students,” President Jonathan Brand said. “And with it came a history of some pretty incredible results.”

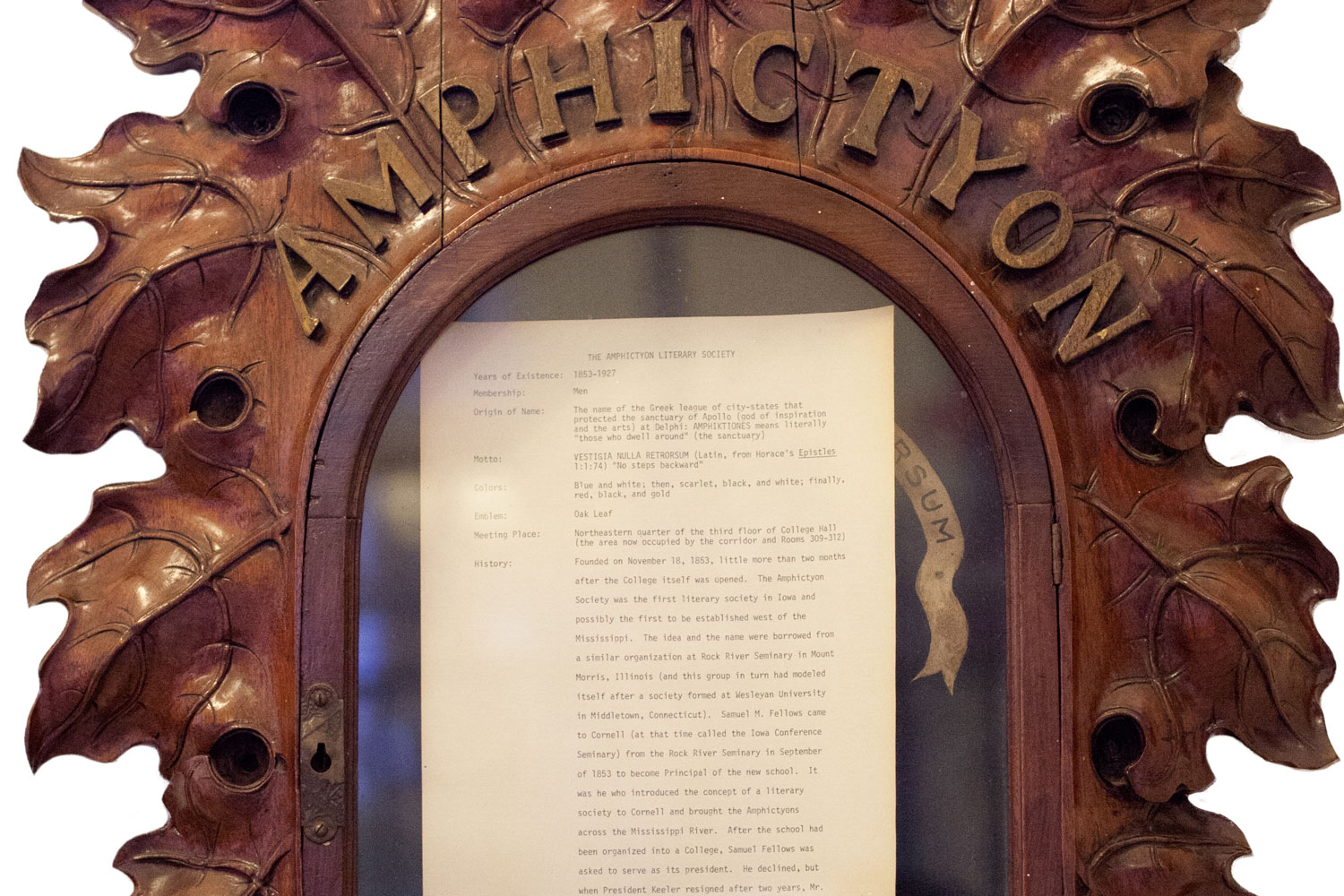

Incredible and historic. In 1876 Cornell won the first ever intercollegiate baseball game in Iowa over the University of Iowa. Less than a decade later, students formed the Cornell Athletic Association and the Cornell Lawn Association in the same year the college as a whole joined the Iowa Intercollegiate Athletic Association. The first Coe-Cornell football game took place in 1891.

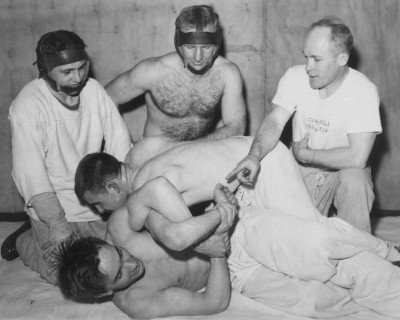

Along the way, Cornell started making the kind of history that defines and informs the Cornell experience to this day. There was the 1947 wrestling national championship, the 67 Midwest Conference Championships across 14 different sports, and the adoption of women’s athletics long before Title IX.

“Being very biased, we have one of the finest athletic traditions, and it’s one I think most small colleges would be envious of,” Athletic Director John Cochrane said.

It was history, believe it or not, that brought senior lineman Sean Langan to Cornell College.

“I knew in the past they were conference champions,” Langan said of the Cornell football program. “Cornell has a pretty good history, and I knew I wanted to be part of that group to get it back in the right direction, get it moving forward again.”

Langan was an “undersized” lineman, clocking in at 6-foot-2, 255 pounds, too small for major college programs, but still big enough to do some damage on game days. So while Division I football wasn’t in the cards, Langan knew he wanted to continue playing the sport he loved. The opportunity to do so at Cornell, he said, was a major part of the attraction.

“It was a variety of things [that attracted me to Cornell],” Langan said. “It’s not just football. Football is what caught my attention and started me looking here in the first place. At the time I didn’t know anything about the academics at Cornell.”

That hook, the opportunity to play sports at a strong academic institution, is a major force in attracting students to the Hilltop.

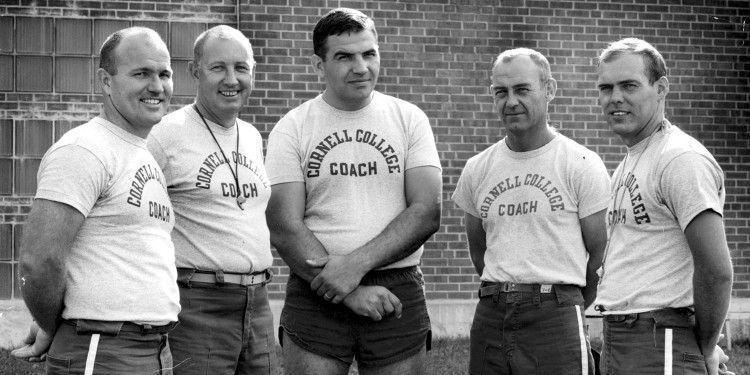

“When I talk to student-athletes and when I talk to alumni who were student-athletes, they almost invariably say that athletics were huge for them,” Brand said. “Their experience is so deep and so profound. It’s one of the purest experiences that our students can have, between the students and the coaches and the students and the students.”

Students seem to agree. Cornell’s athletics program is more important than ever, serving more and more students every year.

Nearly 140 first-year students—more than 35 percent of the class—are participating in athletics, a record as far as anyone in the athletics department can tell.

The 70-plus athletes who came out in the fall for football also represents a recent high for participation, and sports like cross country and women’s soccer also saw large influxes of new players.

Cornell now offers 17 intercollegiate sports, a number of club sports, a range of intramurals, and additional opportunities for our students to engage in physical activity. Basically, there’s something for anyone looking for a way to stay active.

“I think what’s really exciting is that Cornell College, led by Jonathan Brand, in its effort to reimagine the liberal arts experience, has made a very conscious decision to reimagine athletics as a key and important part of liberal arts,” said Barry Boyer ’84, a former football player under Steve Miller ’65.

Part of that reimagining is a reexamination of athletic facilities—specifically the historic and long-standing Ash Park—as a way to reinvigorate the program, specifically when it comes to recruiting, player safety, and the creation of playing space for Cornellians of all stripes.

“From the perspective of student athletes, they’re all looking at facilities now,” Associate Director of Athletics Dick Simmons said. “You don’t have to be the Taj Mahal, but it’s got to be something you want to show recruits.”

Ash Park’s grass fields have created something of a difficulty in recent years. Though the grounds crew carefully tends the field, there’s nothing it can do about the nature of intense, pounding football games being played on a field subject to the weather 24 hours a day. The football team can’t even practice on it for fear of damaging the grass. Instead, they practice in the outfield of the baseball diamond.

“It’s a trickle-down effect. By renovating one stadium, we can have a pretty big effect on two sports,” said Simmons, who also served as the longtime head athletic trainer and has seen more than his fair share of twisted ankles.

Ash Park has long stood as an attractive, useful stadium that drew together students and community members alike. However, some say, time has passed it by.

“When I came back [to Cornell] in ’80, the maintenance people—we had the most primitive painting equipment—they did a fabulous job. They started painting the Ram head and I thought then for years we had the best looking field,” Miller said.

“I thought ours was the best. Over the years that has changed. Now it clearly is not,” he added.

Specifically, the renovation of Ash Park will have an immediate, direct effect on the football and baseball programs. However, the college expects the impact to be much broader than just those two sports.

“Ash Park is one of the most visible areas of the entire college, and providing an all-weather facility to football not only opens that facility up to our sports, but also to our entire student body,” Cochrane said.

He added that he envisions using a turf field to promote and support a variety of sports and activities, including women’s lacrosse, which the current field simply cannot support.

“We really have very little recreational green space on our campus,” Cochrane said. “Now this will become, essentially, a 24-hour facility in those months when there’s not snow on the ground.”

The renovated fields will also close a gap when it comes to attracting student athletes.

“You don’t have to be the number one facility that students are looking at, but you’ve got to be in the conversation,” Miller said, adding that this was true right up until the 2000s, when many high schools began installing artificial turf fields that rivaled or surpassed college stadiums.

Cochrane said he believes Ash Park is just step one in a refurbishing of athletics program. He said he hopes to upgrade men’s and women’s soccer facilities as well as the Small Multi-Sport Center in the future.

“Athletics is not going to be an afterthought. It’s a selling point for the college,” Cochrane said.

It didn’t take long to realize this might be a special season for Cornell women’s basketball. Returning four starters and the squad’s eight leading scorers, the team went on a tear early that included a win over a UW-Eau Claire squad that went 21–7 last season, as well as a thorough (and satisfying) trouncing of Coe.

But it was a 21-point win over the team favored to win the conference for the fourth time in a row that really put everyone on notice. Cornell was a real contender for the conference crown.

The Midwest Conference, that is.

“Our transition back into the Midwest Conference has energized our athletics as well. It’s a new measuring stick for them. I think they’re genuinely excited for that,” Cochrane said.

The results seem to support Cochrane’s theory. Beyond the women’s basketball season to remember, men’s basketball won more games in its first 10 contests this year than it did all of last season. Football went from 3–7 (1–7 in conference play) to 4–6 (4–5 in the MWC). Even volleyball, which went 28–6 during its 2011 campaign, upped the ante by making a second straight trip to the NCAA Division III National tournament despite having no seniors on the roster.

In other words, transitioning to the Midwest Conference after more than a decade in the Iowa Conference has already paid dividends.

“We like to compare ourselves to all the MWC schools, because of the mix and the emphasis on academics and athletics,” Miller said. “It’s been our history, it’s been our tradition.”

In fact, Cornell and the Midwest Conference are intrinsically tied. Cornell was one of the founding members of the Midwest Collegiate Athletic Conference in 1921, a precursor to the MWC. Cornell left for the Iowa Conference in the late 1990s, but came back this year for experiences just like the women’s basketball team is having.

I think their quality of experience will be a little bit richer in the Midwest Conference,” Simmons said.

Long after the toilet paper has been tossed, well past the point when students have gone hoarse and the final buzzers have sounded, once the lights have dimmed and the gym has emptied, students, parents, coaches, and professors are often still buzzing about the yearly ritual, wondering who brought the giant roll or telling friends excitedly how they were totally the ones who got that roll in the basket. No backboard even.

But well after that, the experience remains. So much so that anyone who has thrown a roll themselves could read the introduction to this article and immediately let their mind wander to the school’s rivalry with Coe, despite nary a mention of the nearby college. Because there’s no need to say it. Because the students who shared that experience already know.

“Great athletic programs draw crowds and those crowds draw diverse people, and those crowds have a common bond,” Boyer said.

The common bond—whether felt from the bleachers or the floor, the field or the stands—is something that encapsulates a student’s experience so completely that they inevitably return to it even years down the road.

“Our students learn to rely on each other in the athletic context as well as in the classroom and residential settings,” said Brand. “They learn to take risks, and they learn that the best results come from being a team. When you ask students, when you ask alumni, ‘What do you remember about Cornell?’, they’re going to say they made the best friends of their life, and athletics fosters that.”

Senior basketball player Kat Schilling said her best memories center on the friendships athletics have fostered.

“I’ve built this family. I’m so close with these girls,” Schilling said. “I would come back in a heartbeat to see Coach [Brent] Brase. He’s done so much for me.”

But it goes beyond just her teammates and coaches. Schilling said the entire athletics department contributes to an experience she’ll carry with her for her entire life. “They all know your name. It would feel wrong if I didn’t come back to see people. I’ve had so many advisors,” Schilling said.

Athletics also fosters, Brand believes, a healthier, more well-rounded student inside and outside of the classroom. It’s why the college celebrates its Academic All-Americans so vigorously, and why the college seeks to actively recruit the best and brightest student-athletes it can find.

“What I value so much about Cornell athletics is woven through our coaches. It would be easy to imagine a school approaching athletics as very separate from academics in the school,” Brand said. “That’s not Cornell athletics.”

Brand is a strong believer in athletics as part of a balanced curriculum, a hallmark of the Cornell experience. Besides promoting general health and wellness, Brand says there is value in the goal setting, teamwork, relationship building and the fostering of campus spirit that are inherent in athletics. It doesn’t just make students better athletes. It makes them better people.

For Boyer that includes a lifetime’s worth of memories and lessons learned.

“My greatest memory was playing for the conference championship at Ripon in the snow and being with very good friends of mine who are still friends of mine,” Boyer said. “The athletic experience capped off a great academic experience as well.”

It was that confluence of experience that Boyer said helped make him and so many others the complete individuals Cornell helped them to become.

“I’m a great believer that none of us are self-made. I don’t believe that there’s anyone that came to achieve success all by themselves. Sports are the perfect mirror of life. You realize that you depend on others for the success of your organization,” Boyer said. “It ended up being a great training ground for life.”

Blake Rasmussen ’05 is an Austin, Texas-based writer and former Cornell soccer player. He still plays soccer.