Forgotten Architect Leaves His Signature on The Hilltop

Visitors to the Cornell College campus are met with two massive, castle-like structures that dominate the Hilltop. King Chapel and Bowman Hall, together with two distinctive homes in this community of 4,506, are the work of Cass Chapman, a forgotten 19th-century Chicago architect whose flights of architectural fancy have given this campus its unique signature.

Although not a celebrated architect in his time, Chapman’s remaining structures are landmarks in their respective communities. Indeed, for well over a century King Chapel has been the campus icon and a symbol of permanence and culture to all who approach Mount Vernon.

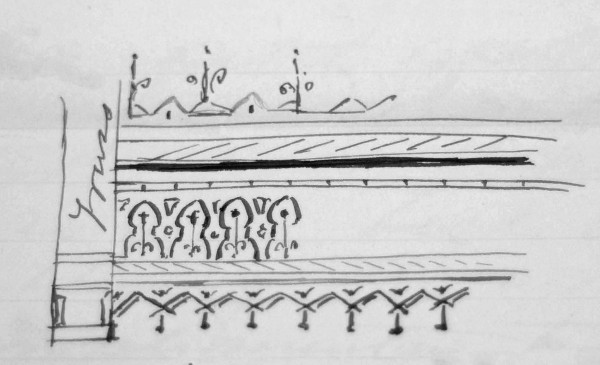

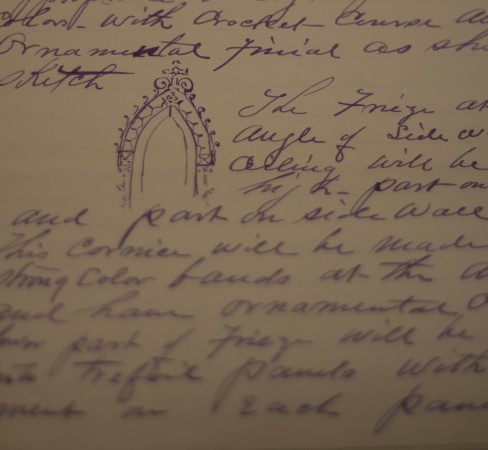

stencil the King Chapel walls and ceilings.

Chapman (1834–1900) was reputedly the first white child born in Niles, Mich., and was named for the first territorial governor of the Michigan territory, Lewis Cass. As an adult, he worked as a carpenter and builder in Niles, served as Berrien county recorder, and was active in local fraternal organizations.

In 1868 Chapman moved to Chicago presumably to work as an architect with Rufus Rose, an architect for whom he had supervised the construction work on a Niles church. Their office was destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, which also destroyed the Lakeside Building, a structure Chapman designed for the R.R. Donnelley Press. Construction had reached the fifth floor at the time of the fire.

Chapman and his wife, Harmony, remained in Chicago post fire. In 1874 he briefly partnered with James H. Place and moved into offices in Jenney’s Lakeside Building in Chicago, the successor to Chapman’s own design.

In 1875 Chapman was hired by Cornell College to design a college chapel—the first professionally designed building on the Cornell campus. The selection of Chapman may have been related to standardized designs he had prepared for the new Board of Church Extension of the Methodist Church, a group dedicated to supporting the construction of new churches and headed by Alpha J. Kynett, a member of the Cornell College Board of Trustees.

Daily services had been held in the building today known as Old Sem, and later, in a chapel room located in the building now known as College Hall. The need for a separate chapel must have been apparent for years to the board of trustees who in early 1874 “resolved that immediate steps be taken for the erection of a chapel building.” Curiously, this action was taken in the midst of a financial panic and while President William Fletcher King, who likely would have prevented the decision, was in Europe.

Upon his return, King, an astute business man, saw the great folly of the board’s decision and the “exceedingly embarrassing situation” in which it placed him as college president. Undaunted, King set to work and, ultimately, brought the project to a successful conclusion, fully earning the honor when the college renamed the chapel in his honor. Chapman exacerbated the situation by estimating building costs at $24,000. When completed, the structure cost nearly three times as much.

Chapman made several visits to Mount Vernon to observe construction. Problems, beyond the control of either the college or its architect, delayed construction for several years. The building contractor went bankrupt and filed liens against the college, funds ran low, and construction halted. The debt nearly bankrupted the college, and in King’s mind, completing the building meant saving the college. For five years the chapel windows were boarded up until a fund drive, inspired by the college’s quarter centennial, raised money to finish the building in time for commencement in 1882, when the building was dedicated.

extensive stenciling, seen in detail in Chapman’s building instructions (below).

The building contained the college’s chapel, library, and museum on the first level, with a large auditorium above.  The auditorium was the building’s crowning glory, a room that Chapman referred to as “without exception one of the finest and largest in the west,” and featured wood paneling, oak pews, and graceful winding staircases connecting the stage to the horseshoe balcony above. Heavy timber beams framed the four gables, rising 45 feet over the auditorium floor. The ceilings and walls were covered with polychromatic series of stencils designed by Chapman. Renovations in the 1920s, 1950s, and 1960s removed most of Chapman’s ornate decorations, leaving little beyond the balcony and the colorful glass windows.

The auditorium was the building’s crowning glory, a room that Chapman referred to as “without exception one of the finest and largest in the west,” and featured wood paneling, oak pews, and graceful winding staircases connecting the stage to the horseshoe balcony above. Heavy timber beams framed the four gables, rising 45 feet over the auditorium floor. The ceilings and walls were covered with polychromatic series of stencils designed by Chapman. Renovations in the 1920s, 1950s, and 1960s removed most of Chapman’s ornate decorations, leaving little beyond the balcony and the colorful glass windows.

On the exterior, the design remains Chapman’s. The mansard roof tower of the chapel, which long ago became the symbol of the college, still reaches, as he noted, “130 feet above the highest point in the county” allowing a view of “towns from 20-30 miles distant.” The other chapel towers have finials and hipped roofs. Chapman had a love for towers: the spire of a Methodist Church he designed in 1878 is, at 185 feet, still the tallest structure in Salem, Ore., and towers feature prominently in most of his known designs. The King Chapel towers are built in both square and circular forms, as well as the distinctive mansard roofed main tower.

During the late 1870s and early 1880s Chapman completed a variety of residential and public commissions.

Two commissions were for homes in Mount Vernon: a large brick house for Cornell classics professor Hugh Boyd, completed in 1877, and a Stix Style frame home for the secretary of the Cornell Board of Trustees, Henry H. Rood, in 1883.

Just prior to designing Rood House (now Cornell’s Paul Scott Alumni Center) Chapman designed a residence for businessman Walter L. Peck at Oconomowoc, Wis. Located on an island, the Peck home, known as “Islandale,” is on the National Register of Historic Places. Another Chapman house from this period, known as the Wheeler/ Woolner residence, was built in Peoria, Ill., in 1877.

(Photos by Jamie Kelly (above) and Andrew Decker ’10 (below))

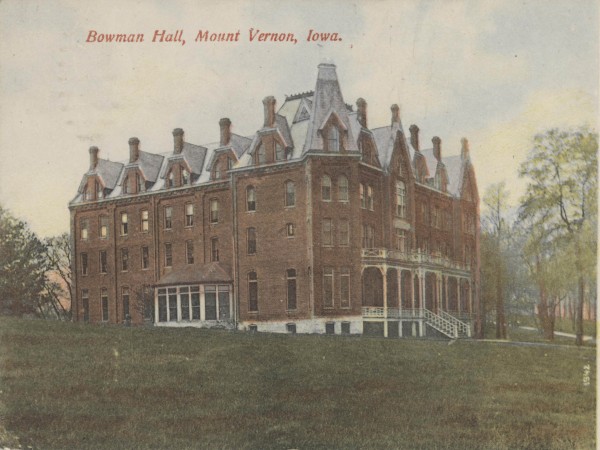

In 1884, Cornell trustees decided that the existing women’s boarding hall, the 30-year-old “Old Sem” building, was outdated and unsafe and commissioned Chapman to design a more suitable building to house female students. What they got from Chapman, two weeks later, was a design for a five-story brick gothic revival palace. Chapman received $833.90 for his services, from a total building cost of $45,261.30. As with King Chapel, the cost was more than double Chapman’s original estimate.

In 1884, Cornell trustees decided that the existing women’s boarding hall, the 30-year-old “Old Sem” building, was outdated and unsafe and commissioned Chapman to design a more suitable building to house female students. What they got from Chapman, two weeks later, was a design for a five-story brick gothic revival palace. Chapman received $833.90 for his services, from a total building cost of $45,261.30. As with King Chapel, the cost was more than double Chapman’s original estimate.

The new building could house 100 women, and featured a fan-shaped conservatory, large dining room and kitchen. A porch, dripping with wooden gothic tracery, ran the length of the building. The first women’s dormitory constructed west of the Mississippi River, it featured steam heat, hot and cold running water, and gas lights when it opened in 1885.

After his final Cornell commission, Chapman continued to practice in Chicago, focusing on churches and residences. In 1889 he designed the First Christian Church building in Warsaw, Ind., refusing to accept a fee from the congregation.

Chapman closed his office in 1895. During his final years, he worked from his Chicago residence.

Cass Chapman died of heart disease in 1900 and his body was returned to Niles for burial. Years of research have failed to locate a single photograph of him.

All of the buildings that Chapman designed in Mount Vernon are now in Historic Districts on the National Register of Historic Places as contributing structures and essential elements in the built environment of a historically significant college. Thus, a strange symbiotic relationship between a man and an educational institution gives significance to both.

Chapman was a monumental builder, whose turrets and towers, stencils and timber framing mark his buildings as flights of fancy, the product of an untrained hand, but of a man with a clear sense of purpose, and a builder whose creations were built to last.